The first time I saw the Glasgow School of Art was at the age of sixteen in a history of art lecture at Salford Tech given by Peter Pester. He was our Art Historian and, like Travis, was far too accomplished to be teaching at such a place. He was brilliant at conveying the magnificence of a work of art. He was incredibly posh and dapper and he made me feel like a total scally scruff bag. But not in a condescending way, his aim was to empower. He just didn't dumb anything down which reinforced how erudite he was and, in comparison, how much I needed to learn. As soon as I saw the slides of the intricate lines of stone and wrought iron with small pulses of colour I thought 'now that's it, that's what I want to do'. I can still remember it. I remember the feeling. The stretched verticality emphasised by black lines and spots of glowing paint or coloured glass looked (to me) much like my work at the time - I was fascinated by computer chips and circuit boards and glowing lines, think of Tron. When I eventually studied there I fell more in love with Macintosh's other side - the functional side of the school, which in some ways is more impressive: its aim being about conceptual completeness as opposed to the decorative quality of the more extrovert areas. For example, in the basement where not many people went, long cream shelves would kick up, fly over the top of a door, then drop back down and curl into a box. What a way to terminate shelves, most people would just stop. Doorways are usually set into a timber box, a spatial experience, never just a door. And my God - his furniture. If I ever had a problem with my own work I'd walk around looking to Mackintosh for answers. He never let me down, there was always a spatial sequence, a threshold, a detail or a piece of structure which miraculously dealt with whatever problem it was I was struggling with. And that's why it's a masterpiece - because it transcends style, time and function - forever contemporary and relevant. Every part somehow relates directly to its whole - I'd be stuck with a door problem and the answer would be found on the ceiling. It didn't matter where you looked - magic, mysterious. This week - the fire, the library and chicken run lost. It's probably hard to fathom for people who haven't been to the Glasgow School of Art, and it's surprised me too, but it feels like such a loss. I know it's only a building, but a huge part of my history is wrapped up in those spaces which taught me so much. Only last week James Reed and I were discussing going up for the degree shows to see our old friend and look at its new neighbour by Steven Holl. I feel for the students who were setting up their degree shows, again it's difficult to explain the uniqueness of what it means. The degree show openings have an electrified atmosphere. I imagine the damaged areas will be meticulously recreated, which will be right for people who didn't see the original. It's the only possible response, I'd do the same. But for those of us who spent a lot of time there, it's gone forever. Strangely I wrote a post about this a couple of weeks ago - 'Everybody Knows'. If ever there was a building that generated that mysterious quality - it's the Mac. I doubt even Charles himself could recreate it. I watched a Peter Eisenman lecture a couple of days ago and he said something which got me thinking. He always does. One of my favourite points from a few years ago was how sculpture and architecture swapped their position somewhere around the beginning of the twentieth century. Traditional sculpture had no particular location - set on a plinth, a kind of universal level separated from the ground - ground as earth. Modernism in Architecture transformed the ground into a universal plane, a never-ending grid - a surface which slid under architecture, taking with it the very notion of place - and the edifice of inside and outside. In reverse symmetry Modernism in sculpture saw the plinth evaporate as works became site specific, contextual, even environmental - think of Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty. Sculpture left the Plan.

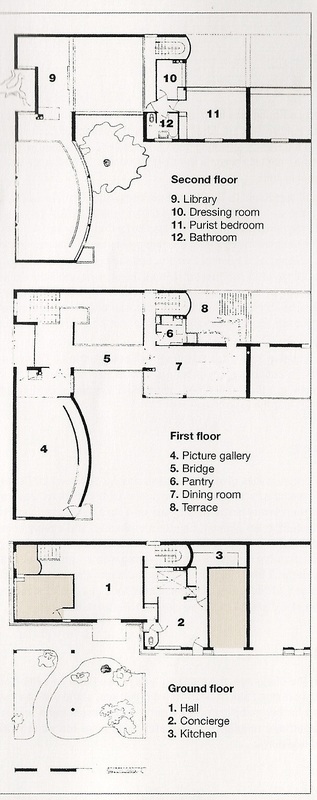

Anyway back to the present... Eisenman was talking about the importance of the plan and aggregation - how he layers various geometries to form an unorganised whole which critically says something about existence... About thirty years ago I had a great teacher (there have only been two so far) called Travis Isherwood. God only knows why such an intellect was teaching at Salford Tech. I was only sixteen on a foundation course in art and design. He taught me many things including life drawing and he could actually draw, I mean really draw, or see as he would put it. For his education he'd spent four years life drawing, every day at the Royal Academy. He was about sixty, so traditionally trained. He taught me about Michelangelo and Leonardo and Ingres and Picasso, he knew everything there was to know about Art and History. He treated me like I was an idiot and would laugh mercilessly at my misunderstanding of everything he would blow my mind with. He wore a black eye patch and would cackle like an old pirate. But I didn't care one bit, all I wanted was access to the secrets of the universe I'd craved all my life. You see he didn't just know about Art, his main interest was Architecture. He'd sit for hours demonstrating how Le Corbusier's Modular proportional system could be used to determine the most functional height for a chair and how it encompassed the Golden Mean, function and aesthetics fused. He told me about the Greeks and the Parthenon and its connection with Le Corbusier. I heard for the first time 'Less is more'. 'My God' I thought, of course 'Less is more'... In the back to backs of Salford Architectural Philosophy isn't really discussed! The 'Plan is the generator' Travis said, quoting Le Corbusier, this is the sentence I was reminded of from thirty years ago. This is kind of what Peter Eisenman was saying - although he sees it in a different way which involves lots of French philosophy which is very difficult to define. My simplistic interpretation is that it's something to do with the convention of the plan as an internal logic belonging to the Discipline of Architecture with a capital 'A'. As if the plan is a formal, critical tool which can be used to unlock the meaning of Architecture as a Metaphysical Project - is it really there? and, if so, what is it? My interpretation at the age of sixteen was given away by my response: 'So do you mean you can feel the plan when walking through a building?' I asked. Eisenman would hate this response. He is at war with Phenomenology. And I think for all the right reasons. Although I love the fetishisation of materiality, as I love Zumptor's work, I still want Architecture to be about the discipline. A culture with History/Time and syntax. It's just too fascinating - to only think about the sensory experience of a building seems far too easy. And if you look at Jacques Derrida whose Deconstruction philosophy is a part of Eisenman's investigations, his aim was to reveal Truth by deconstructing the very context of a system - the binary oppositions set up to form an idea. Or what some Modern Spiritual thinkers call 'This and that' or 'The relative world of opposites'. So yes I'm back to the mystery which 'Everybody knows' and can only be not talked about by talking about something. The something is the plan. At the weekend I read a review for a new book about Mies Van Der Rohe, it was in a Sunday paper supplement magazine. Isn't it incredible he's still making it into mainstream consciousness when his last building was completed in 1958?

It seems the 'Truth' does survive and persist. I won't go into what I think the 'Truth' is - we all know it when we see it. We might not like it, depending on how seduced we are by our particular delusion, but we definitely see it. As Leonard Cohen says 'Everybody Knows'. I remember the feeling I had when I first saw the Barcelona Pavilion designed by Mies for the 1929 International Exposition. I was 20 and in total identification with Le Corbusier. The day before I'd been to Villa Roche and a few of Corb's other buildings in Paris - you have to appreciate that all this was brand new to me and I didn't fully understand the unique and universal significance of Le Corbusier. In my innocence I thought it was normal to find things in the world which resonated so deeply. After all, my beloved gas cylinders were parked right outside my bedroom window for most of my childhood. Anyway back to Mies. In comparison to Villa Roche, the Barcelona Pavilion felt mean and empty. This worried me for many years. How could I not enjoy a building by someone who was so clearly in 'Truth'? All the drawings, photographs and writings I looked at confirmed I was missing something. The answer was revealed when I visited the National Gallery in Berlin. And this is where it gets a bit esoteric and therefore problematic. The difference is - the Barcelona Pavilion was rebuilt in 1983. Having built many projects over the last twenty years I believe something mysterious happens on site when ideas and drawings become tangible objects. The Barcelona Pavilion is a copy and is therefore devoid of that mysterious quality, that feeling of visceral authenticity I felt in the National Gallery and also later in the Seagram Tower in New York, also by Mies. The strongest I've ever felt it was in Arne Jacobson's National Bank in Copenhagen. I wasn't a massive fan of his architecture from the books, I thought it was all about his amazing furniture. God was I wrong. When I walked into that bank foyer I had an inexplicable and immense opening of the heart and mind. Perhaps it was because I wasn't expecting anything and so my conditioned mind was preoccupied elsewhere. The proportion of the volumes, the exquisite soft light....I must stop attempting a definition, better to describe it in the negative - it had whatever it is that is missing from the Barcelona Pavilion. I had an amazing teacher at university called Drew Plunkett. Again, at the time I didn't realise how rare such people were. I saw him years later and we had an argument. We were stood in Macintosh's masterpiece The Glasgow School of Art. He had just completed an article for a Japanese Architecture magazine. His essay gave the formula for how to create amazing space. Drew said he knew by rational deduction how to recreate the Macintosh studio we were stood in by including various elements and proportions. It sounds so simple. And I think Drew just wondered why the hell I would bother to contradict him on such a rational proposition. And this is the fundamental tension within architectural production. I have spent most of my career navigating a safe path for my projects through vast seas of empty rational justification from all the various parties involved in the realisation of a building. The reason this force is so powerful can be seen in the fakery of the Barcelona Pavilion. The conservationists behind it only meant well and who could argue against their pure intentions? Mies is the absolute epitome of rational order, what could go wrong? The bigger question all this is alluding to is the systemic copying of Mies all over the world. Surely the proof that something mysterious and unrepeatable happens couldn't be more evident in the dead Miesian Order Architecture that inhabits most of our cities? |

Maurice ShaperoMy personal blog Archives

August 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed