|

“I love music too much to live from it.” This is a quote from Carlos Paredes, a recognized genius of the Portuguese Guitar who kept his normal day job. This resonates deeply with me. And reminds me of Paulo Mendes da Rocha who didn't have an architecture practice, but created sublime architecture and won all the big prizes like the Pritzker. He would collaborate with ex students who had set up offices. His art was architecture - not running a business.

There was an article in The Guardian a couple of days ago about AI 'Wiping out architects'. I speak to AI every day. It's like having an assistant. Currently it makes a lot of mistakes and flat out lies, but it takes me down roads I might not have gone down - Roads I don't have the time or the inclination to research, analyse and write about, as it does in seconds. Carlos chose to make feeding himself and his family a separate endeavour to making art. For some artists creating can only ever be a pure process, so delicately balanced on the edge of a knife. A world to be entered voluntarily with full commitment from a place of love. Necessity and time have no place in this world. AI can beat the greatest human chess masters easily. People still love to play chess. It might not go this way, but my hope is that AI can wipe the business side of architecture away for people like me. It will probably also create incredibly beautiful architecture. But that won't stop me, like it doesn't stop people from loving to play chess. One of my clients researches widely, thoroughly and tenaciously. He thinks deeply. My job is to somehow hang a building onto a hook that not only moves, but constantly changes shape. I'm convinced he would be doing this anyway, some people are just creative, but he does have a good reason. And it's a reason that effects all of us without knowing.

My client has been on a journey involuntarily experimenting with various living conditions to see how it effects his health. It began by accident. An undiscovered leak in his bathroom had grown a hidden spewer of airborne toxins - mould spores. Upon moving out he immediately noticed a difference to his health. The Americans were called in. Two amazing experts who know, scientifically, how buildings make us ill. Bill and John. Could they have been called anything else? I'm designing my clients own home. We've already been out to tender. What do you do when you find that what you've specified will make your client ill? The Americans want men in spacesuits to clean everything. To create an airtight, sterile environment. None of the new materials can have anything in them that could become food. Getting these materials in the UK is proving to be very difficult. It's looking like my client's family in America will buy the materials there and ship them over. The Americans sympathise with poor me for having to live in such a backwards country suffering its lack of healthy materials. I feel a twinge of shame and say god bless America. My client then moves into a new build house in Manchester city centre. He has it tested it for mould. All clear. After a week his health plummets. The Americans aren't surprised. A lot of the materials we regularly specify are full toxins. Over time they off gas into the spaces we live and sleep in. What's kind of interesting is that this process has forced a more rigorously beautiful design. We can't use ply (formaldehyde) or glue in the floor. This has lead to a beautiful solid oak floor screwed down to the joists. Glued floating engineered boards are out. We're going to work with an enlightened carpenter for furniture and kitchens etc. who only uses natural methods and materials. The bathrooms will be made from a material that's inherently antibacterial - the tiles and the sanitary ware. There's a clarity and solidity that comes from cutting out all the unseen nasty padding materials. And my client will be able to live in a sanctuary where his immune system is not constantly on the back foot. Although I don't apear to suffer from exposure to these toxins, who knows how it might be affecting me? When the project is finished it will be interesting to see if it feels any different. I'm predicting it will. Tony Trehy recently introduced me to the Artist Marsha McDonald. Marsha will be creating fictional work for a fictional art show, in a fictional art gallery in Tony's fictional world. Marsha once lived in Japan. She said something interesting to me - 'but part of me is in Japan'.

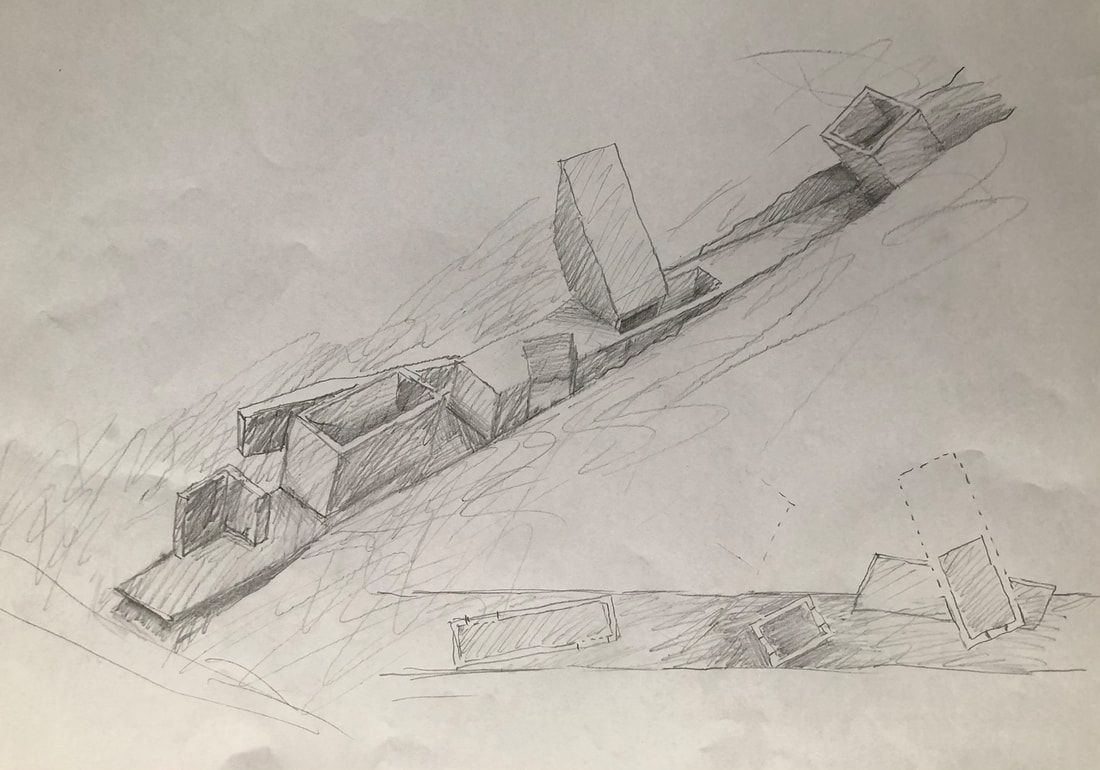

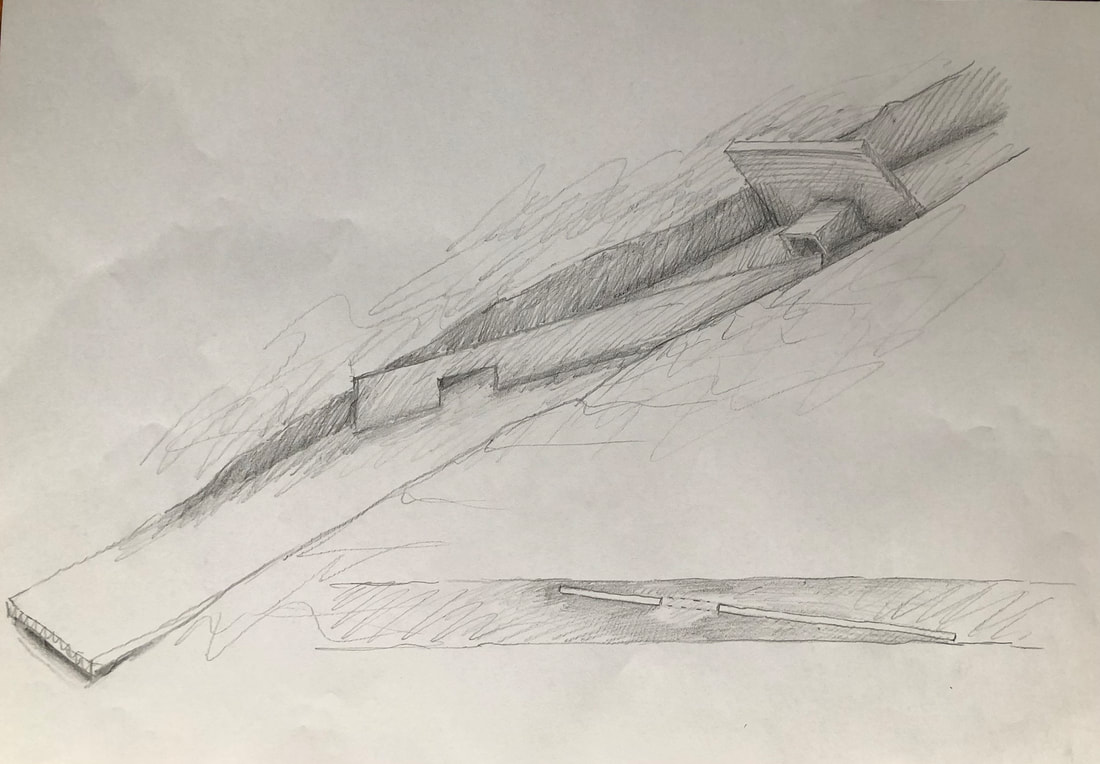

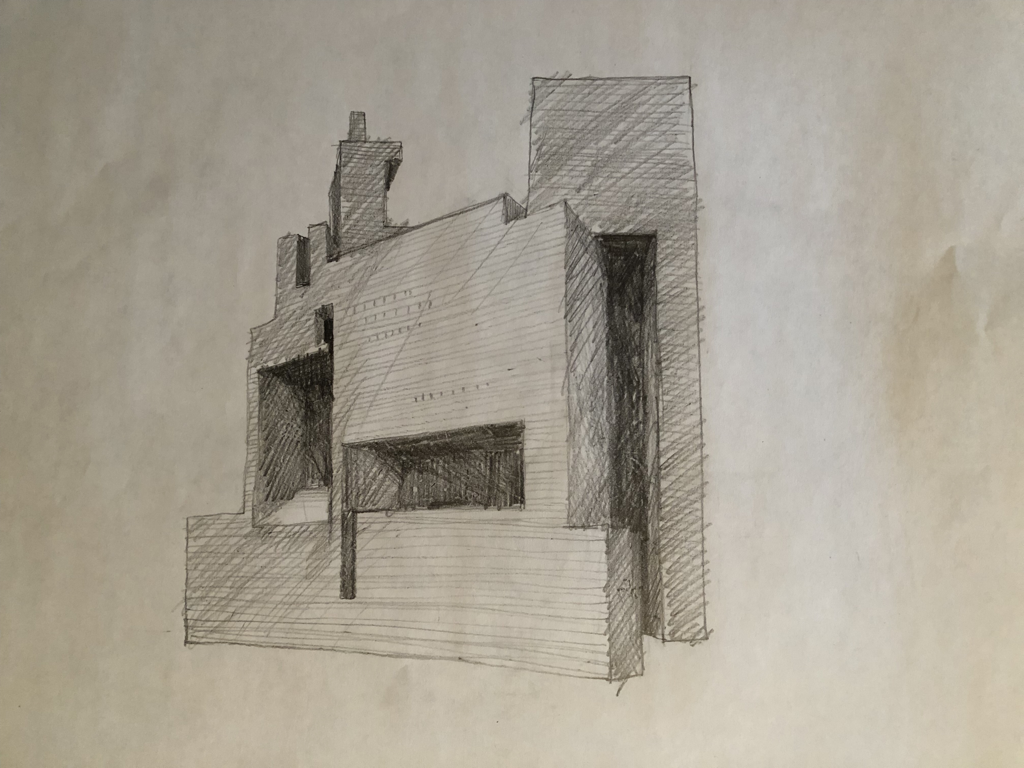

I was very drawn to Japan as an early teenager. The mystical elevation of discipline and technique in all fields. Even the making of a comb transcends into a spiritual practice. Zen made a lot of sense to me. Mainly because I began studying a Japanese form of karate at the age of 13. I still practice it now. The removal of intellectual conscious thought, surrendering to the flow of the ever changing circumstances of combat. I loved the idea that it was even possible to methodically train towards this lack of structure. It was no surprise to me when I started studying architecture that the same esoteric forces were also alive in contemporary Japanese design. So I sort of know what Martha meant. But in a different way. When I visited Japan in 2001 I felt like an alien. I spent a month riding the bullet train looking at contemporary and traditional architecture. I had some sublime experiences. My god - the Ryoan-ji stone garden blew my mind into a million pieces. And Ando's Church of the light - what is there to say? I also had a profound moment with Monet's waterlily's at Ando's Oyamazaki Museum in Kyoto. A project you can't possibly understand from photos (drawings maybe - if you know drawing). I didn't penetrate Japanese culture at all. But I do resonate with their Art - Art in it's broadest sense encompassing all of existence. Across culture and race. As can be seen in Rothko's apparitions. I first met Tony Trehy in 2007. I designed a competition winning art gallery as part of a masterplan for Radcliffe town centre in North Manchester in collaboration with Sir David Adjaye and Urbed. Tony was going to be the director of the gallery. Within minutes of our meeting we were talking about the space between objects, proportional systems and grids. All in relation to Ulrich Rückriem's stone sculptures which were going to be placed in and around the new gallery. We spoke each others language. Tony is a poet and writer. He was also the director of Bury Art Museum until he retired and moved to Porto in Portugal at the start of the pandemic. He curated his final show in 2018 with myself and artist Sarah Hardacre. You can see some photos here. After the show we worked on a book together where Tony wrote poems inspired by my pencil drawings. The brilliant John Rooney designed the book itself. Tony is about to write another novel. It's called The Museum Quarter. To my utter delight he asked if I would prepare a conceptual sketch for one of the museums in the book. The Art Museum. There's something special about this request. I don't fully know why yet, but I do sense a kind of inevitability. I designed my first gallery in 1997 on my kitchen table with detail paper and a pencil. Little did I know then that it would be the only one I would build for the next twenty five years and counting. Over those years I've lost count of the many art gallery's I've designed for competitions all over the world - they all live in my imagination only. And the one I built - Cube in Manchester - has also gone. It was turned into a bar in 2015! Designing a fictional gallery for Tony's book has a radically different feeling to a competition. You would think it would be the same or at least similar, but they aren't. The energy of a competitions is something like this - me pushing my ideas into the world hoping that people who know nothing about me will choose me over others. Not the purest of processes to put yourself through.

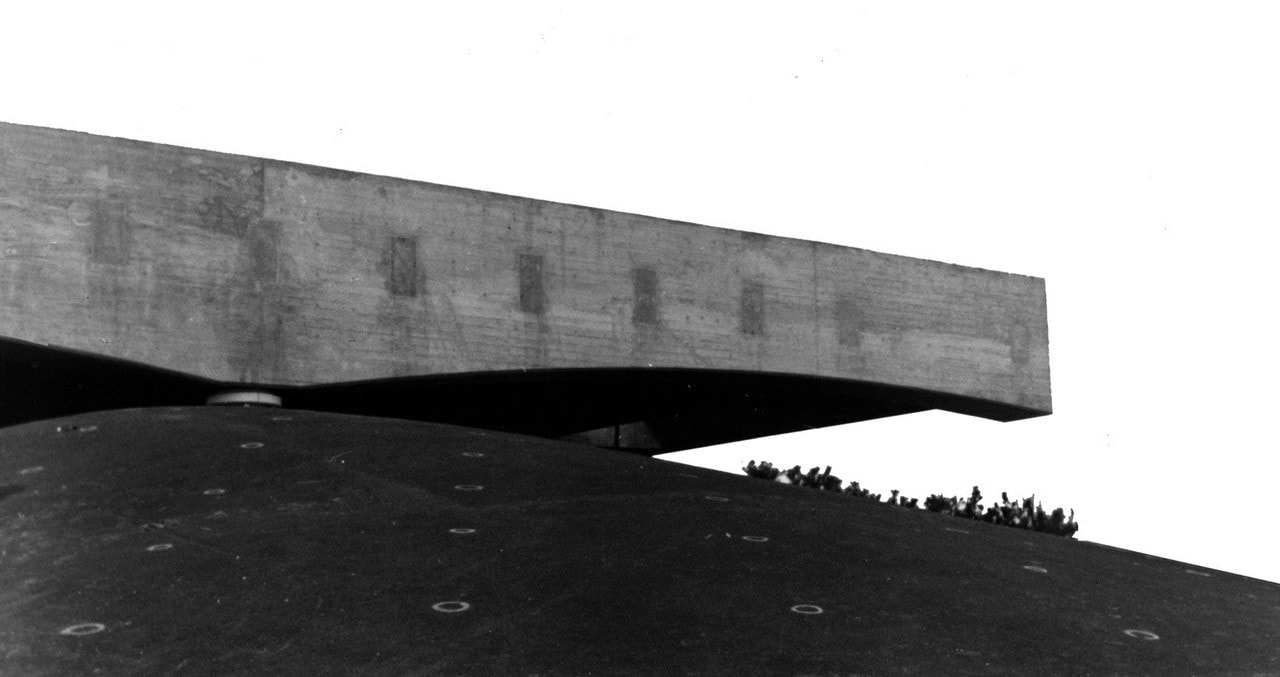

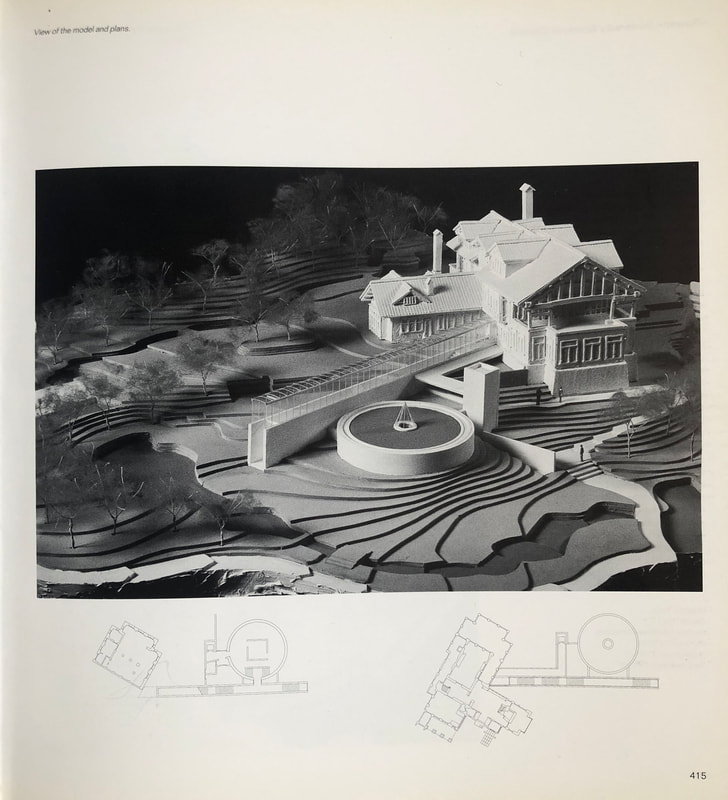

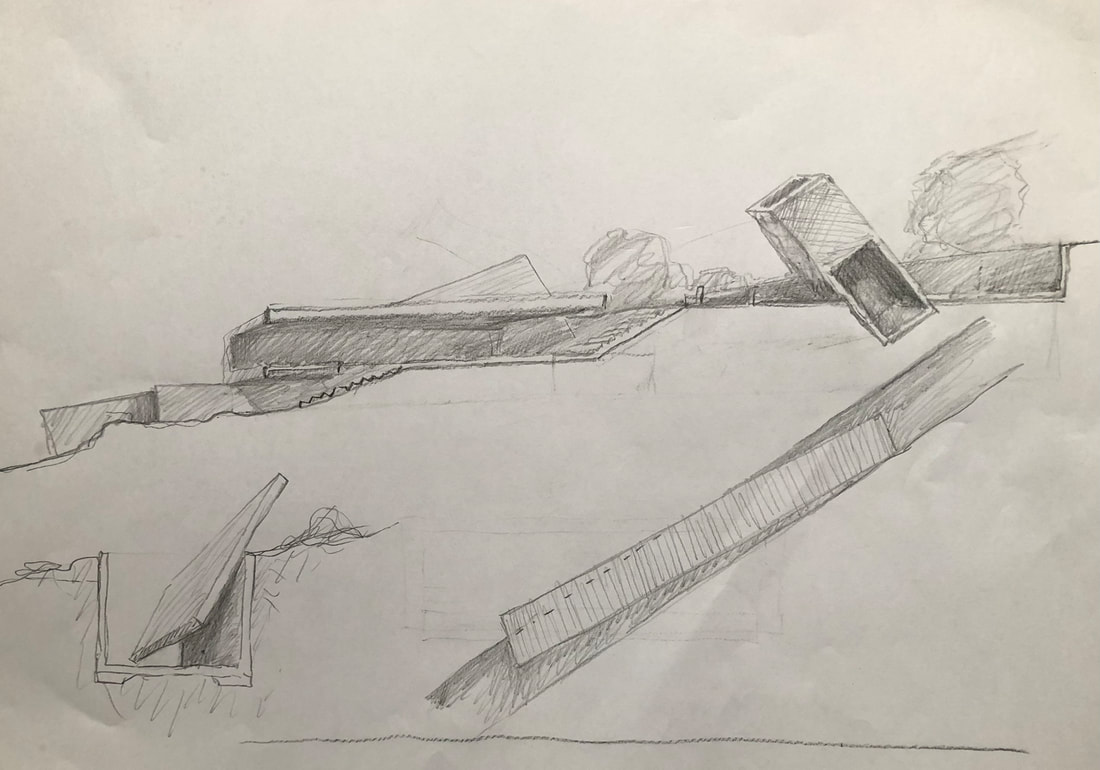

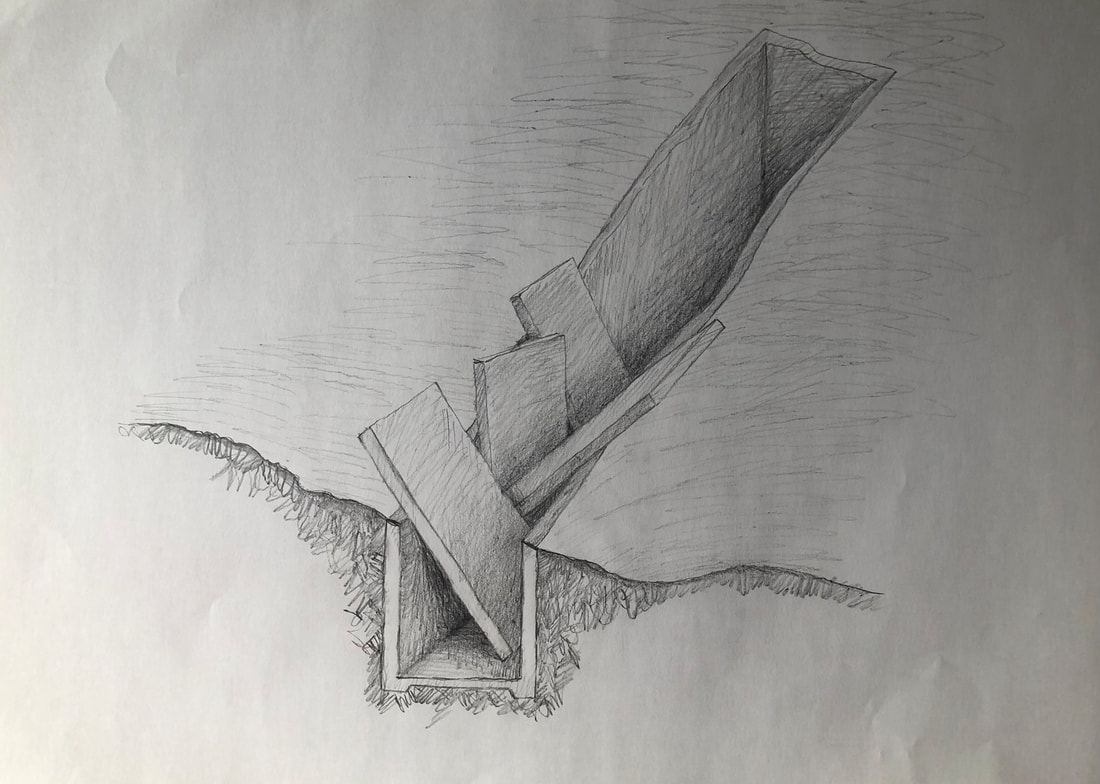

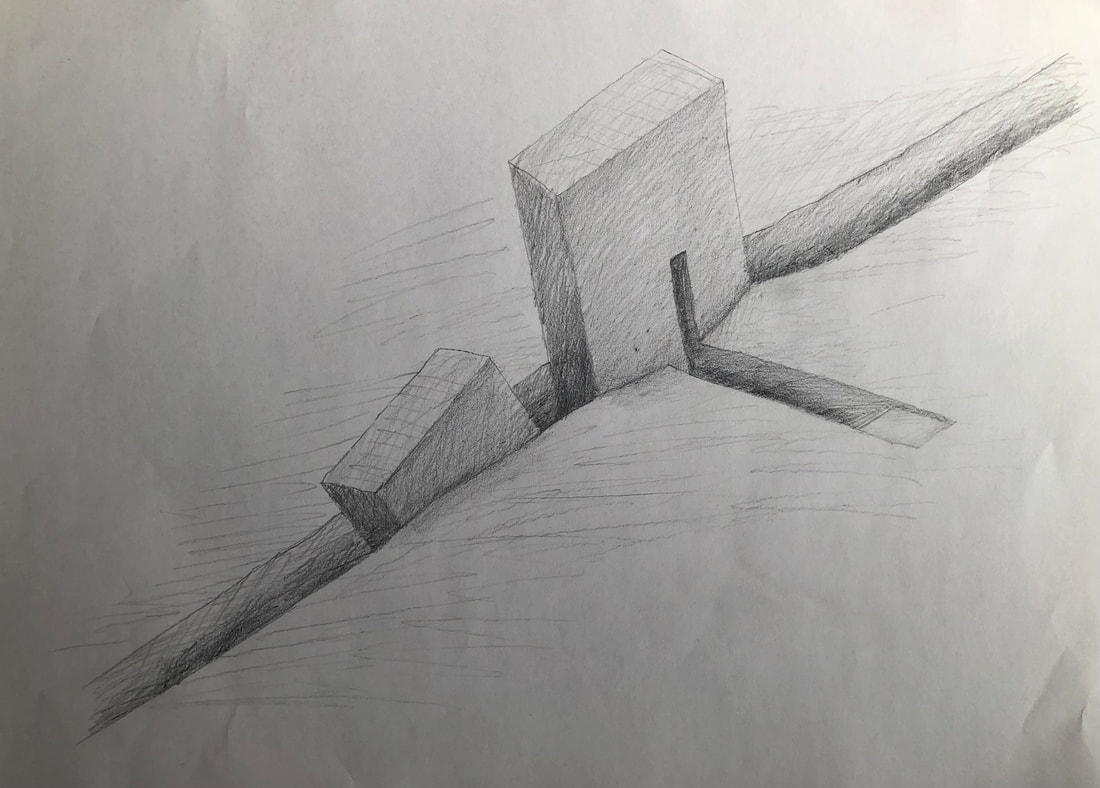

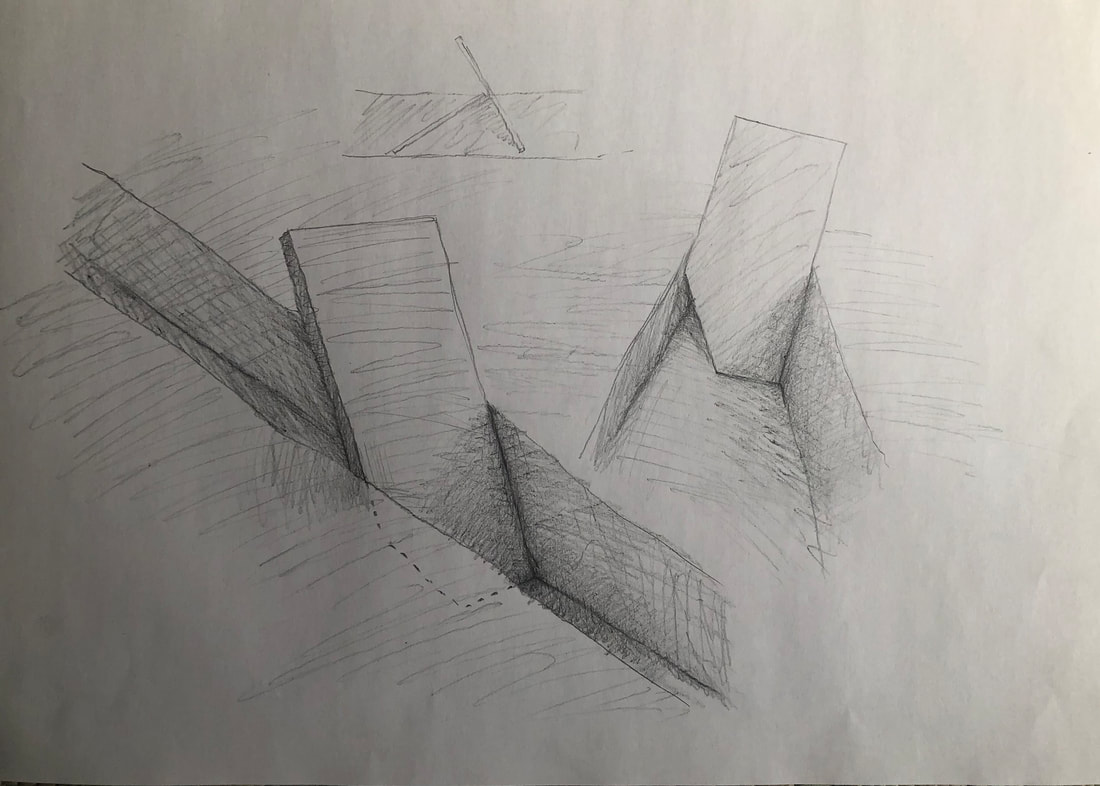

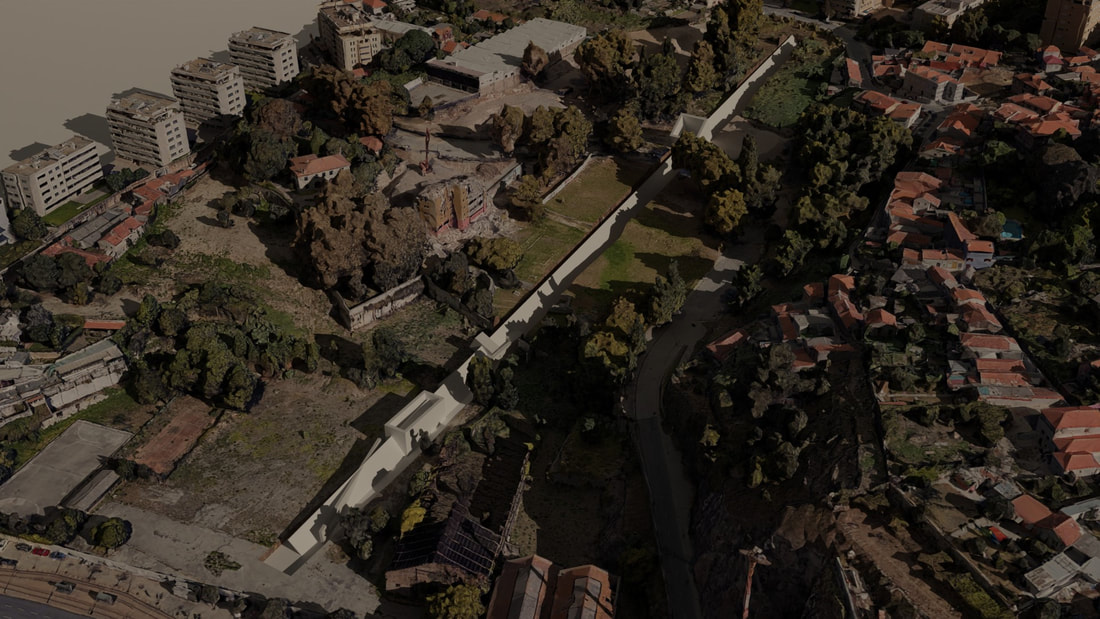

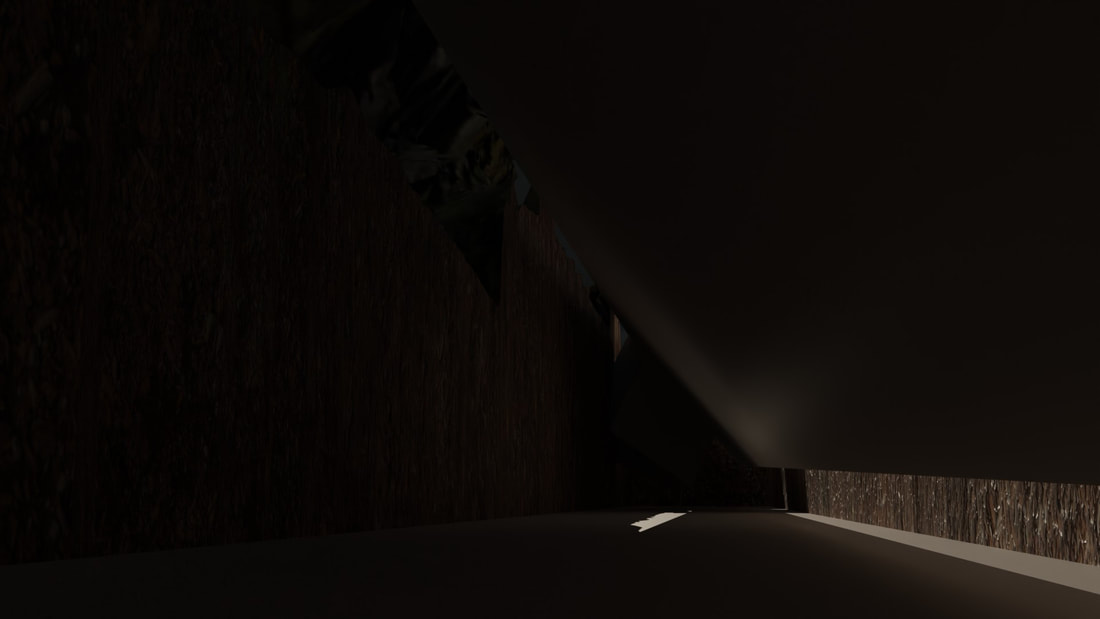

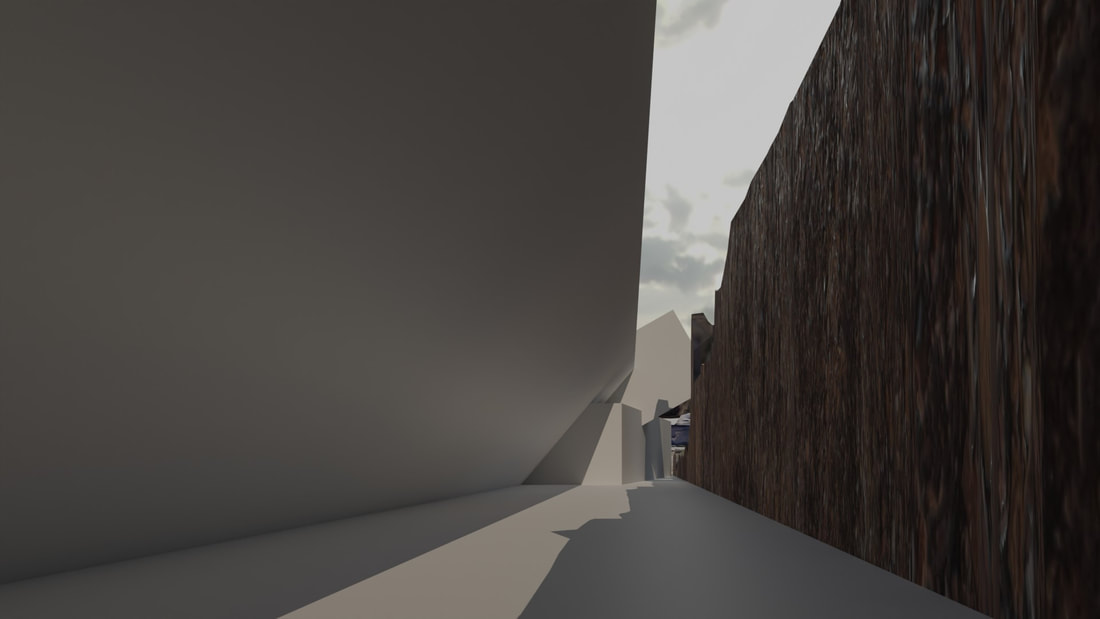

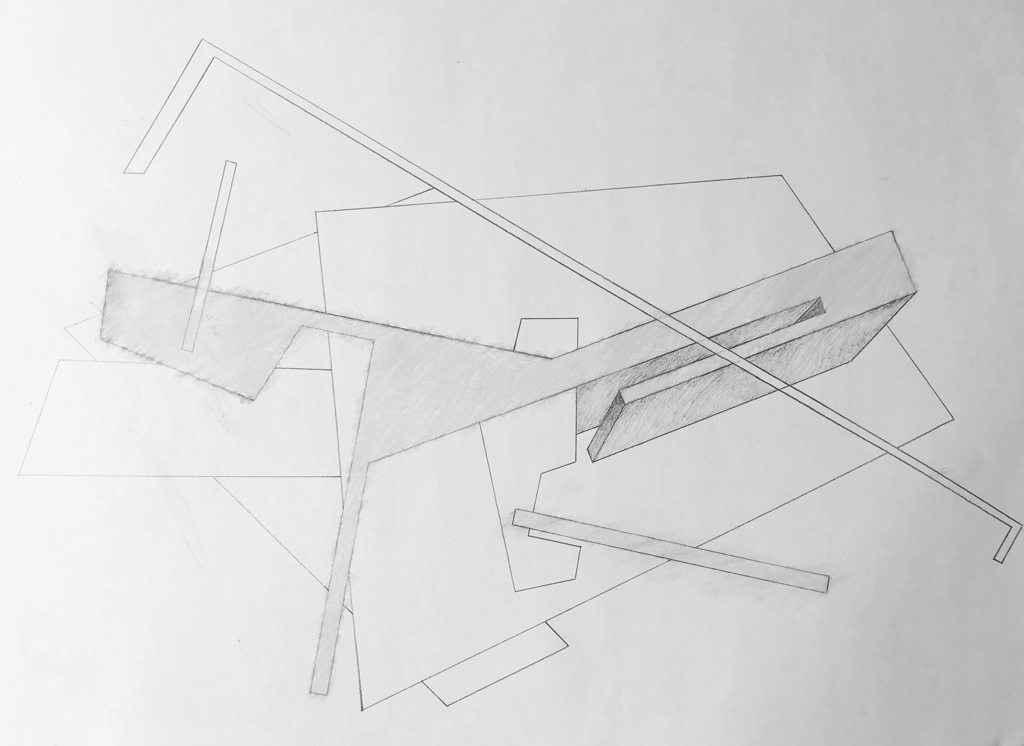

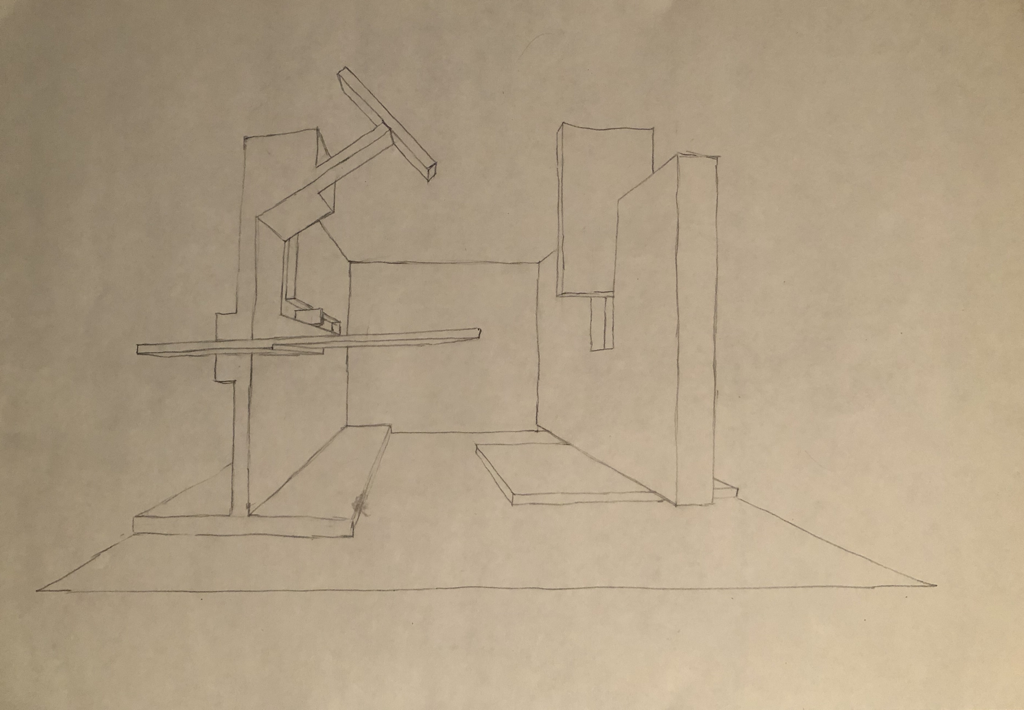

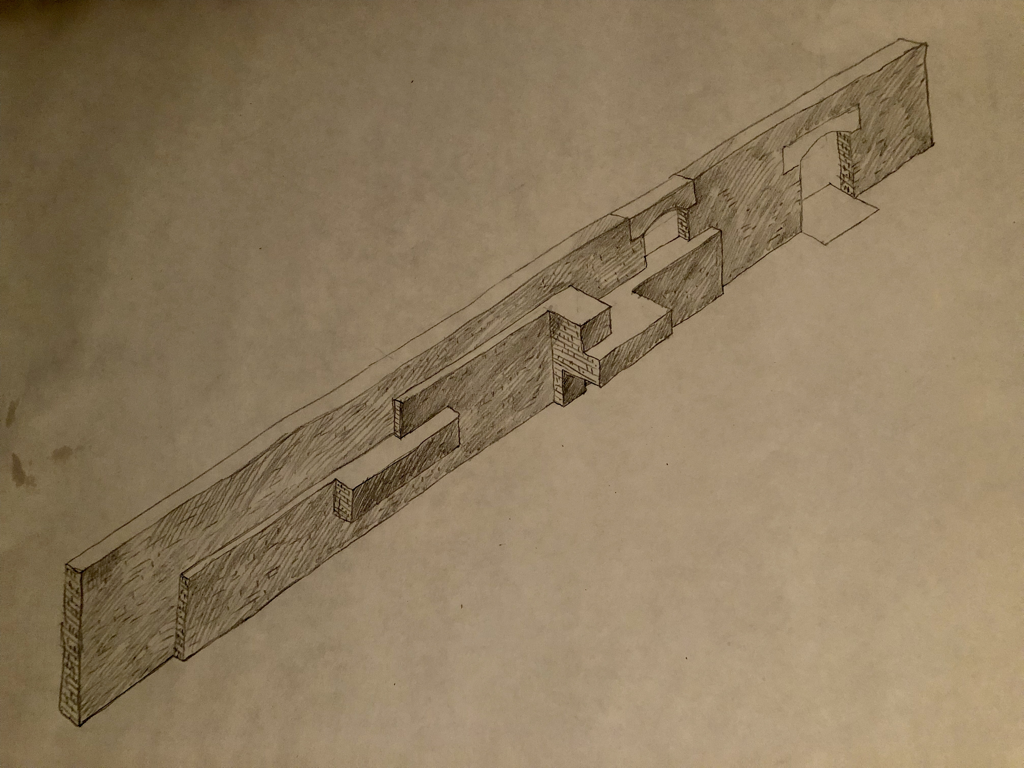

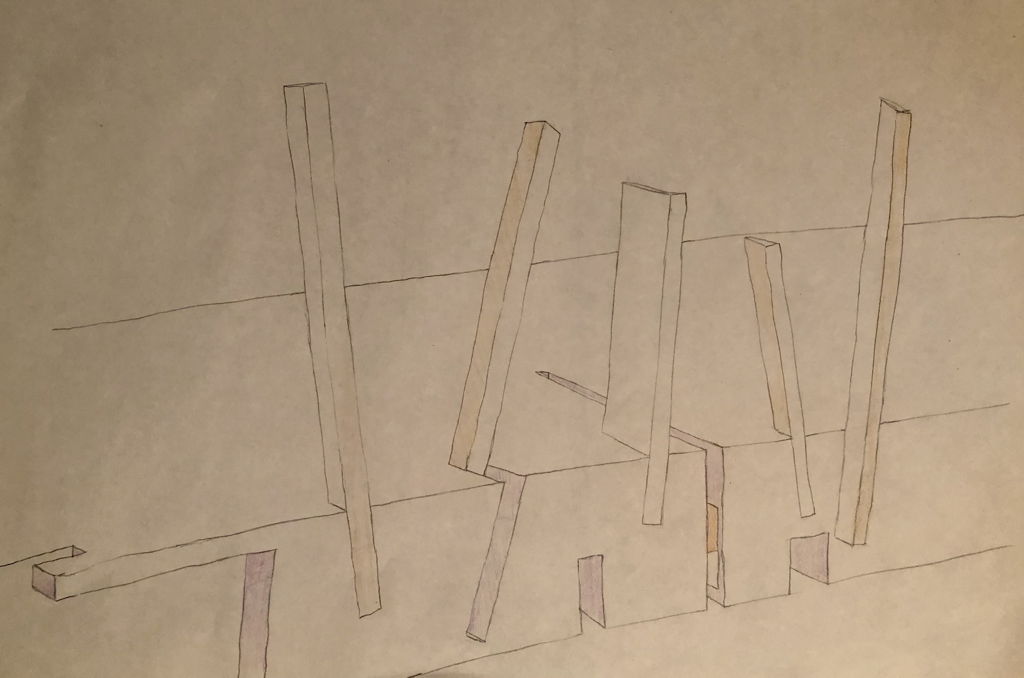

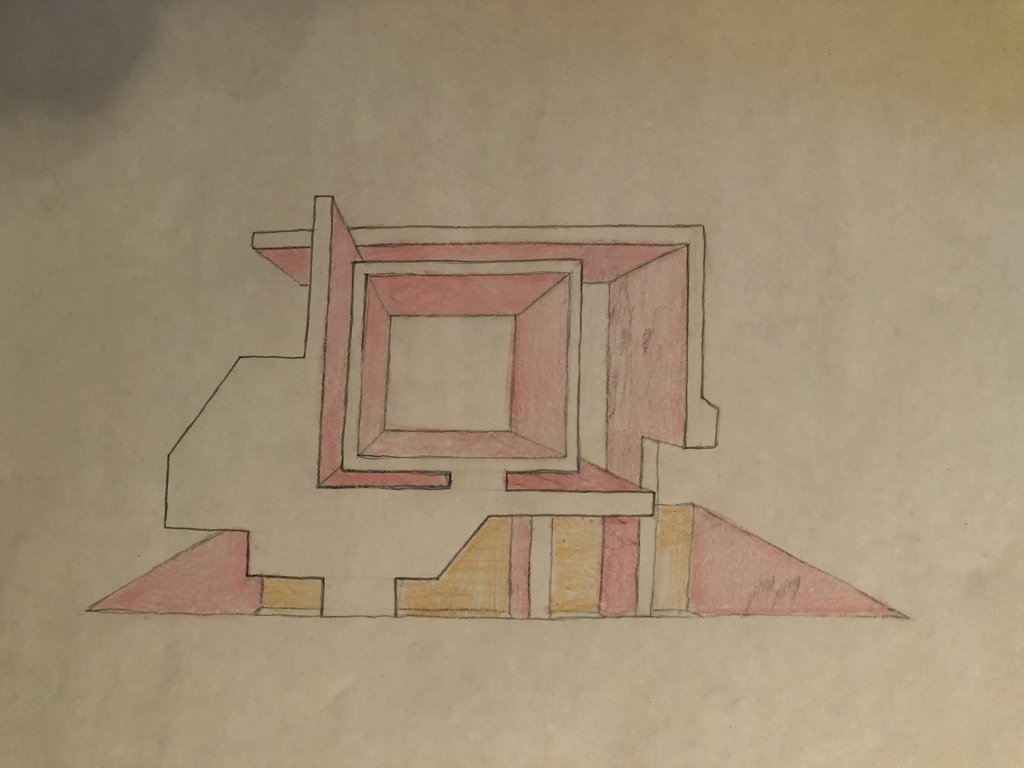

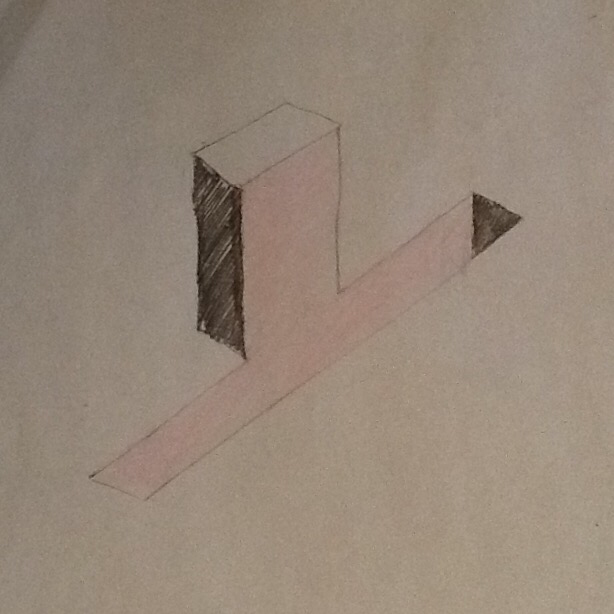

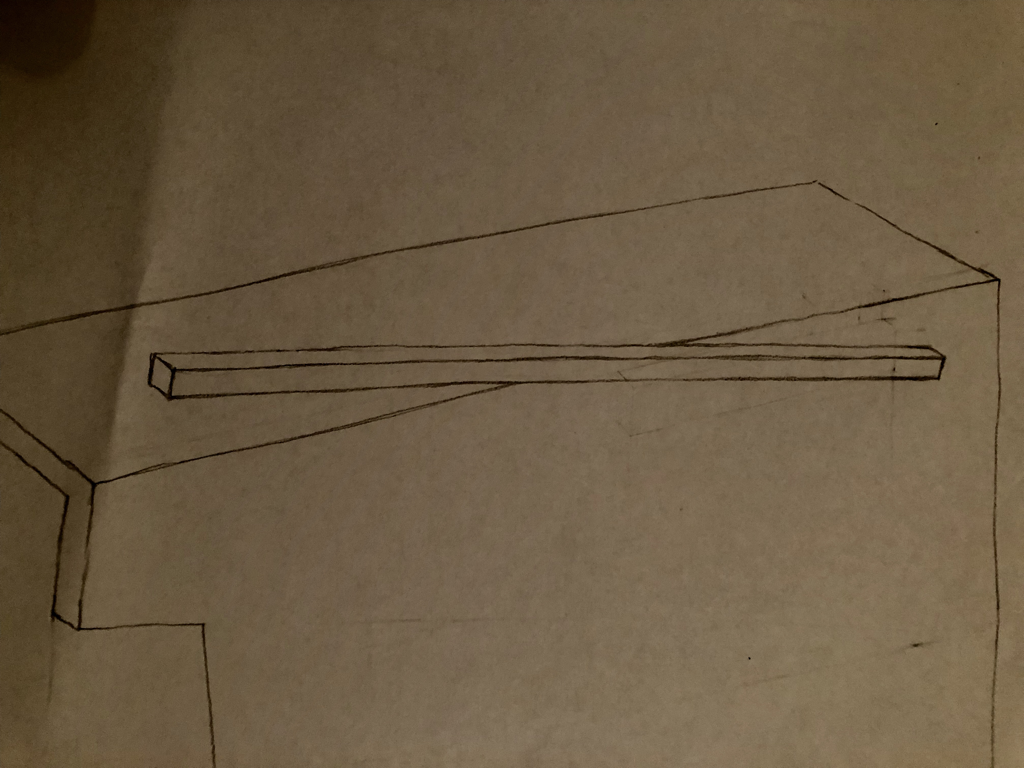

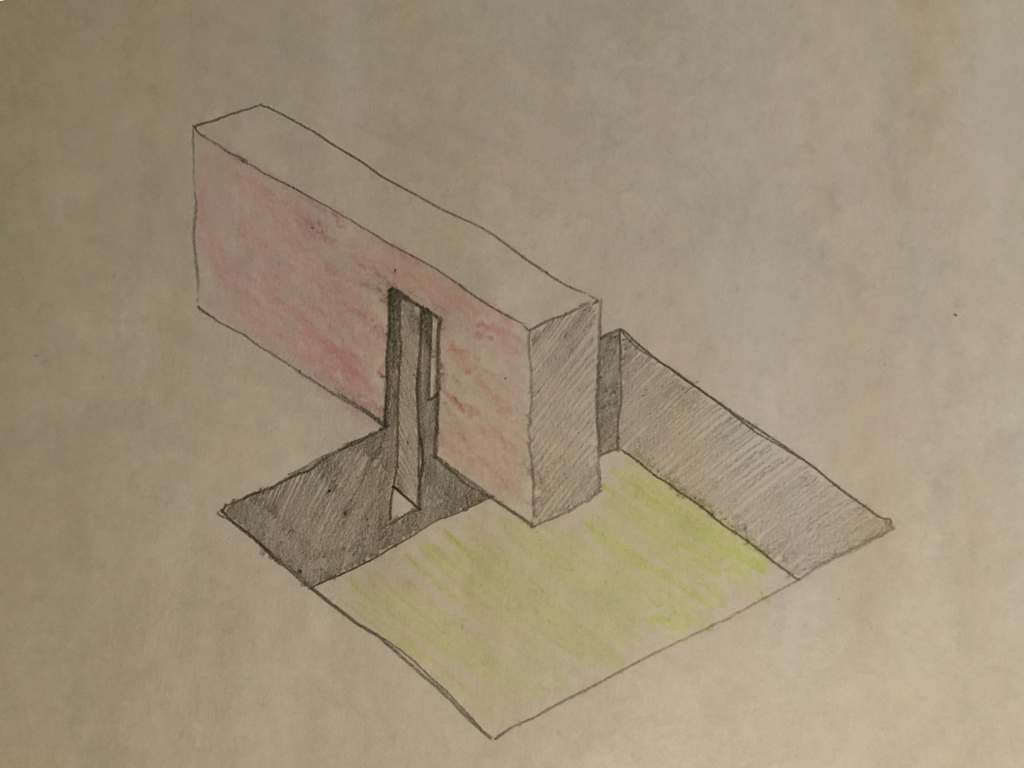

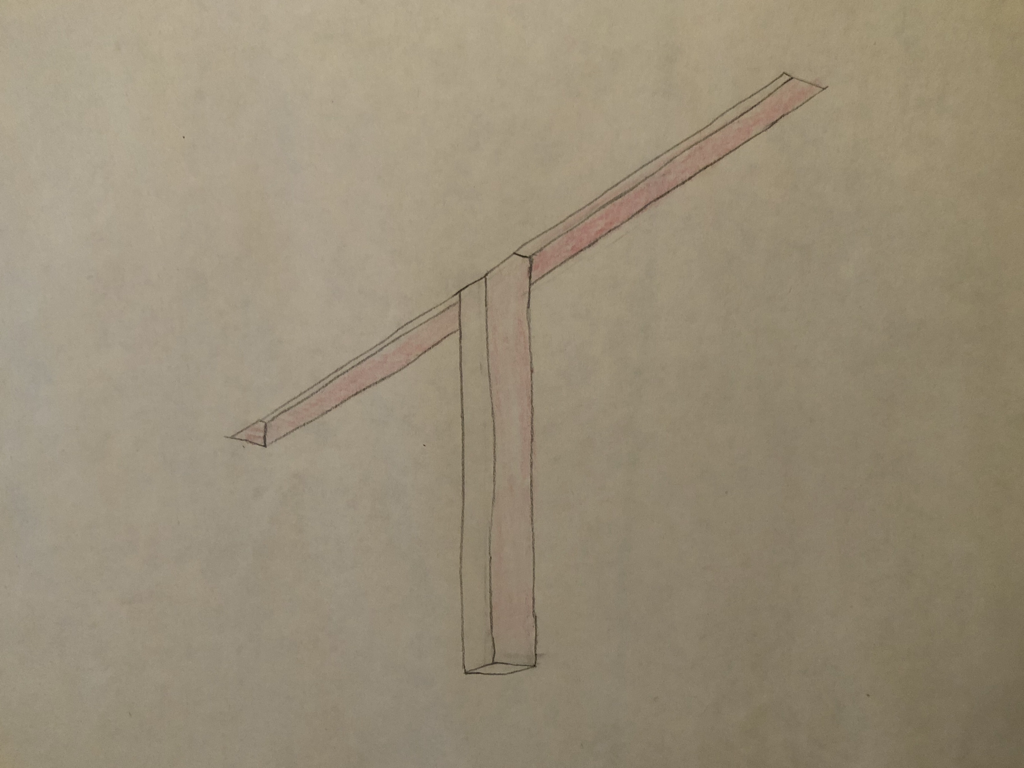

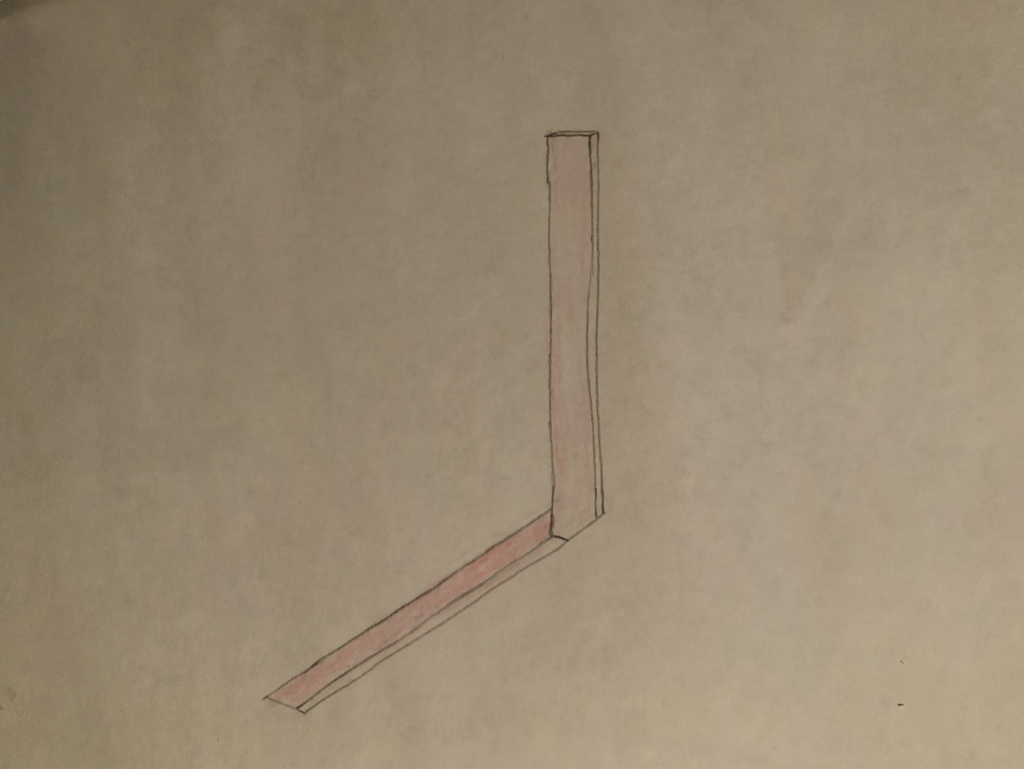

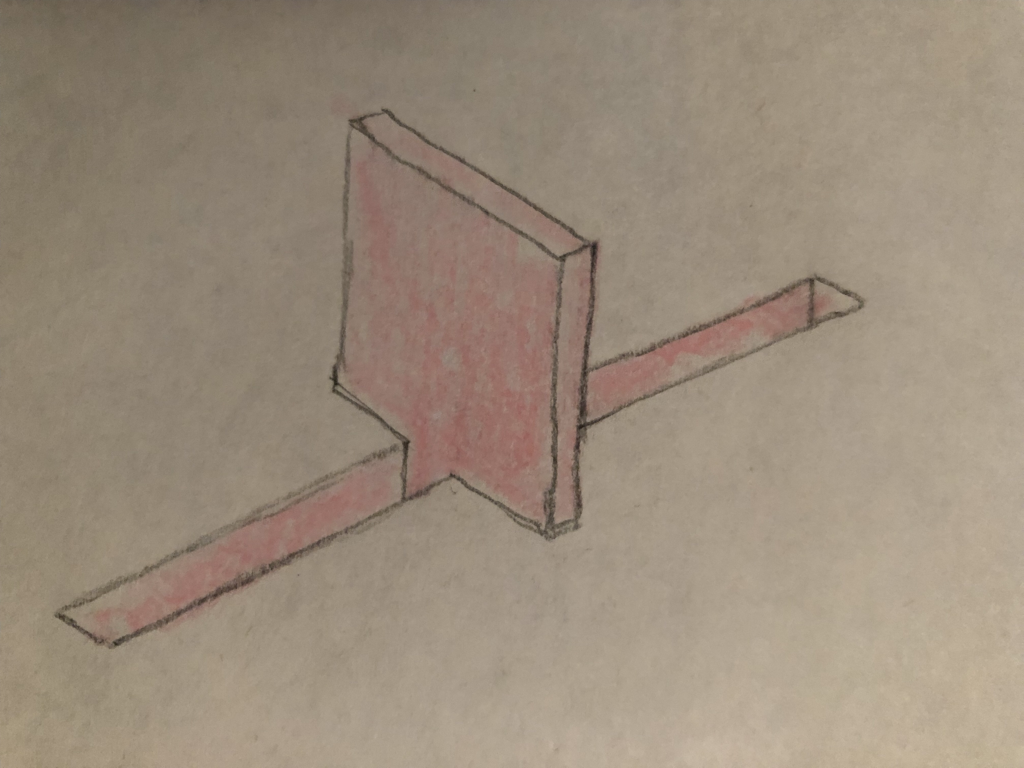

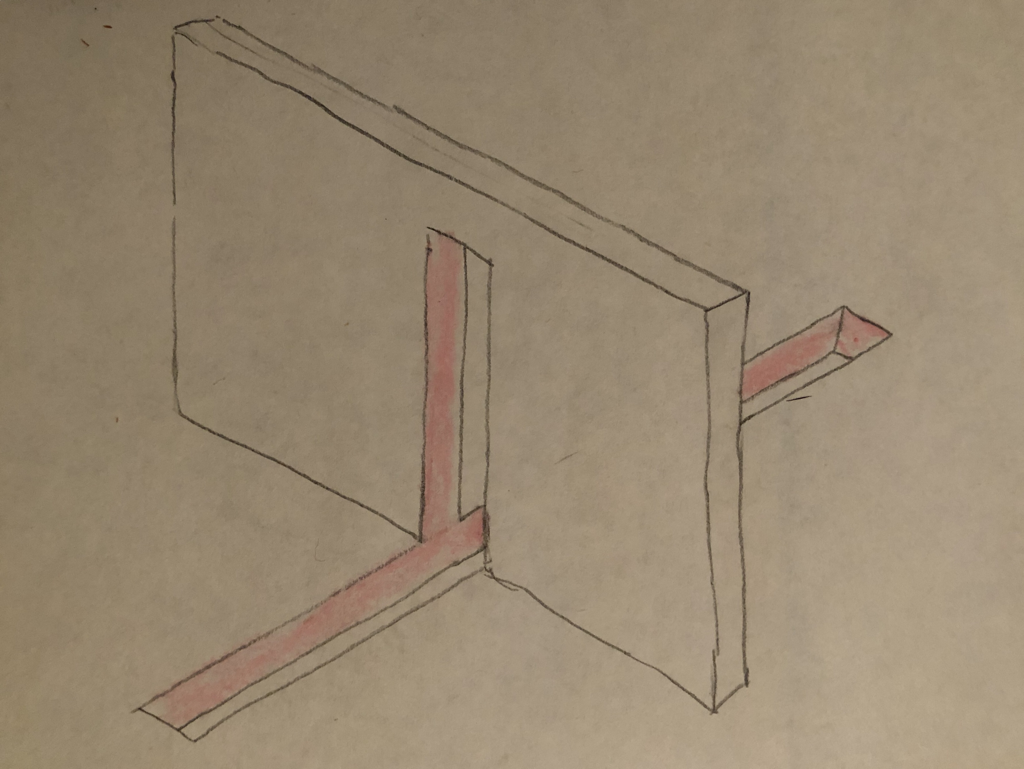

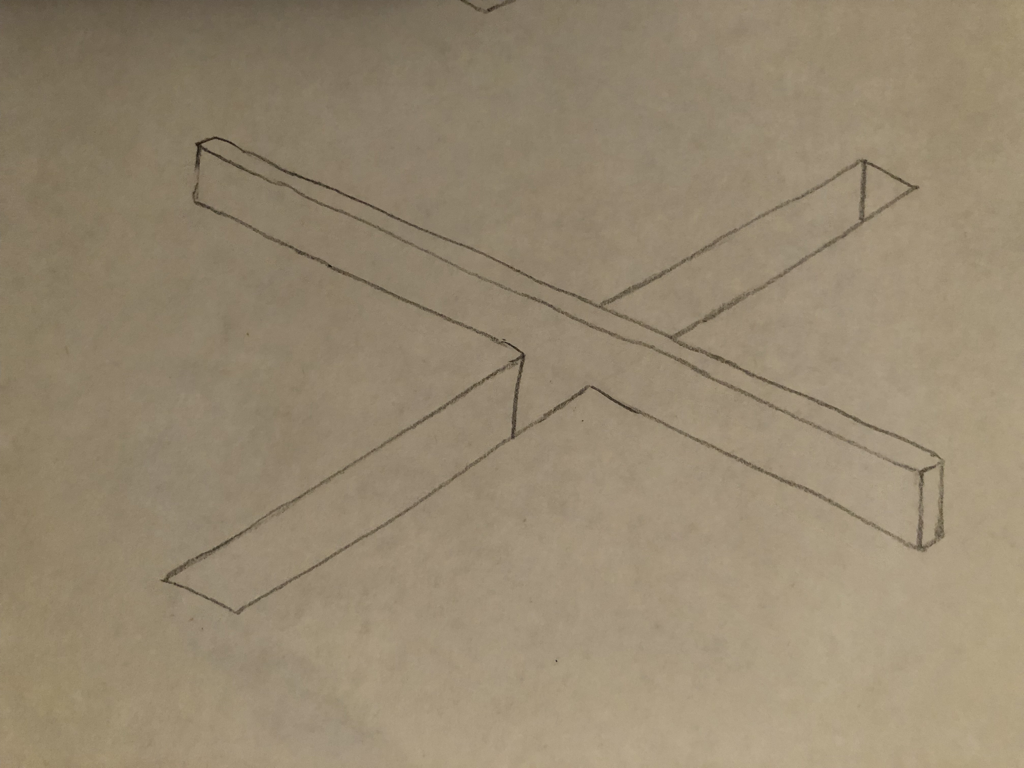

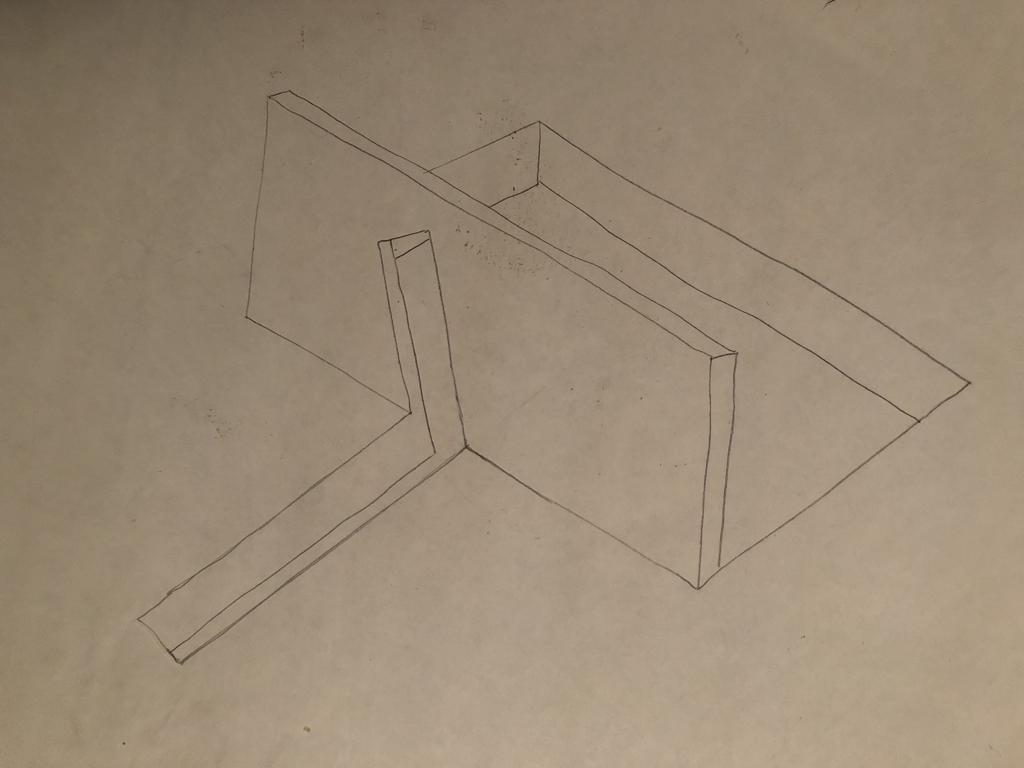

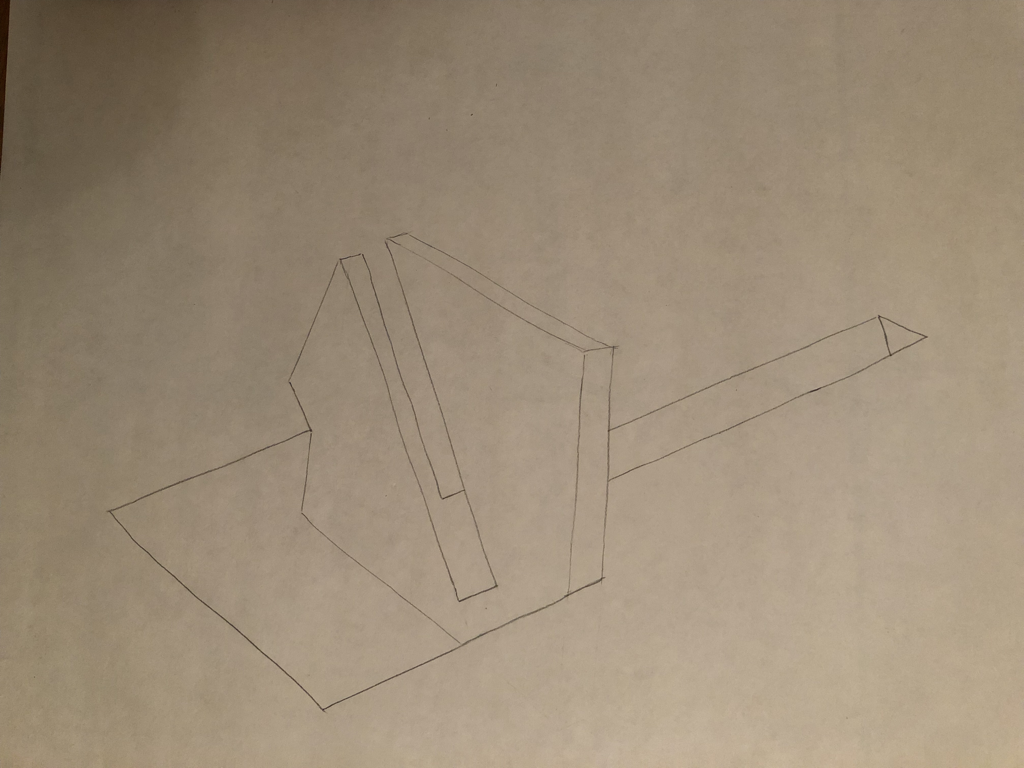

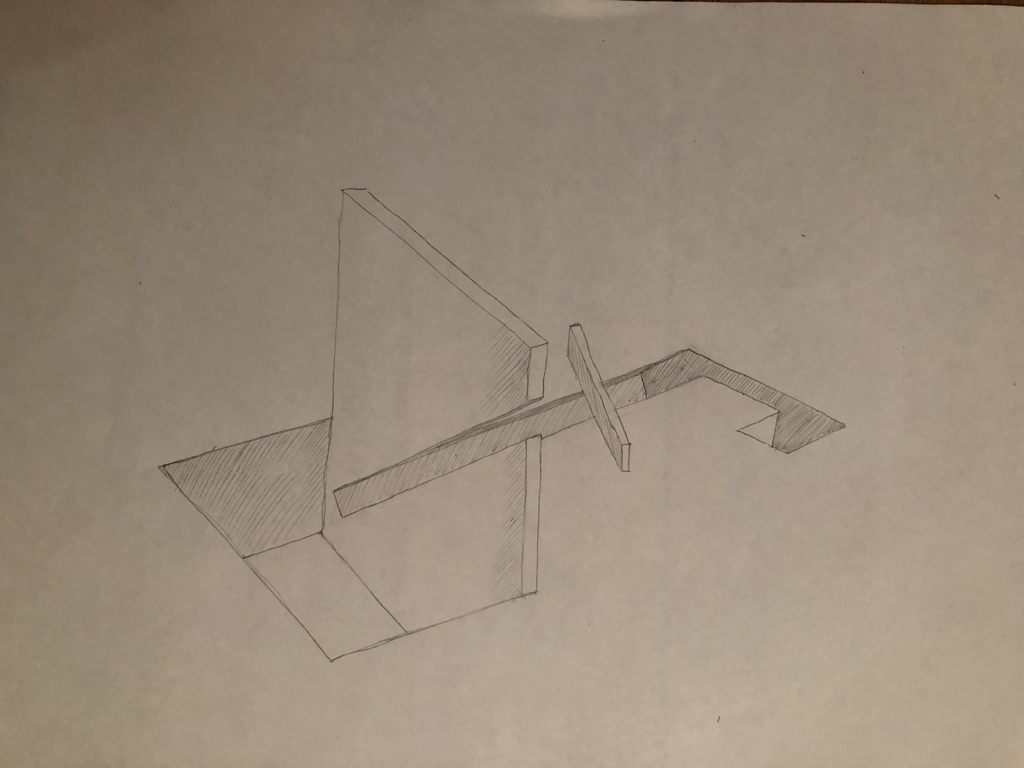

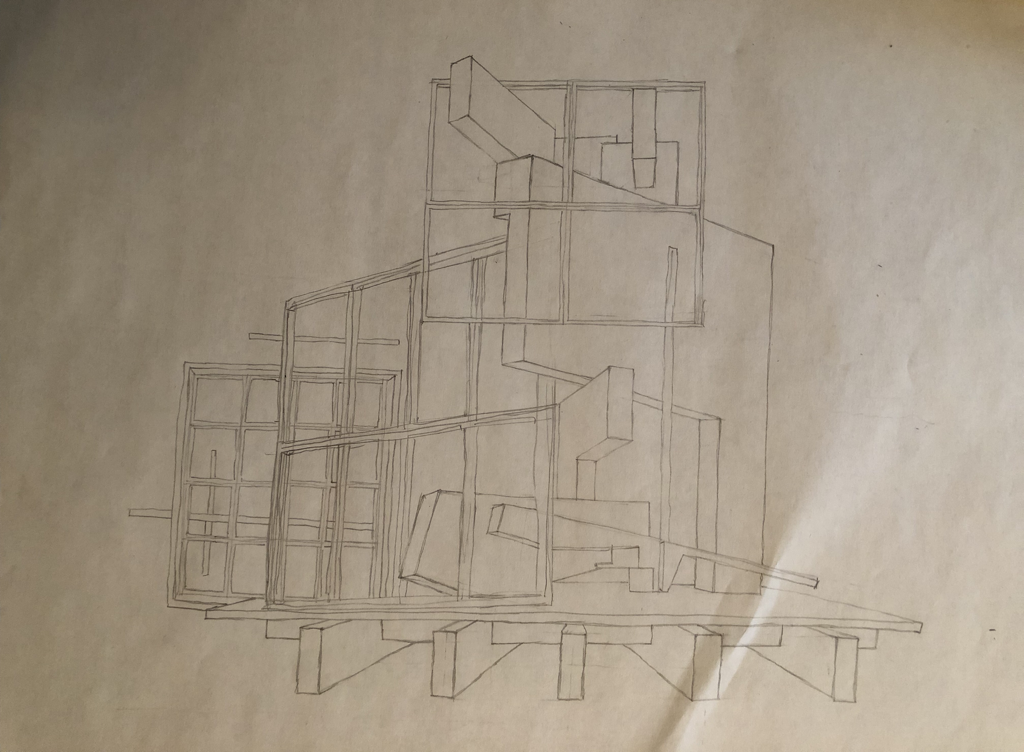

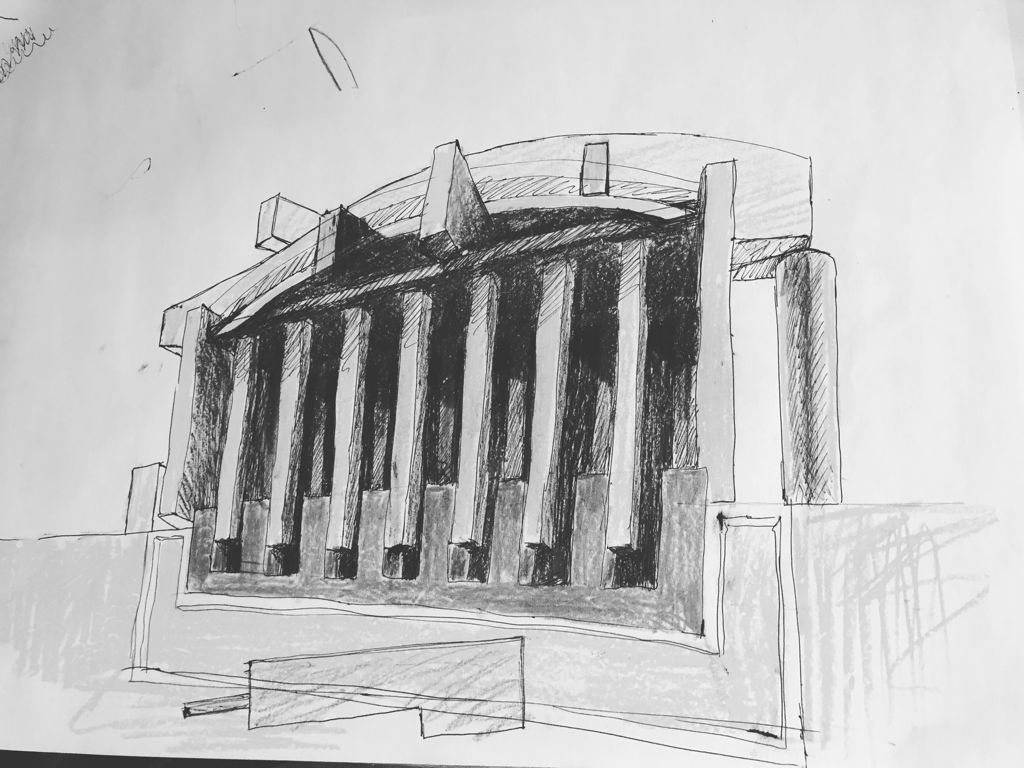

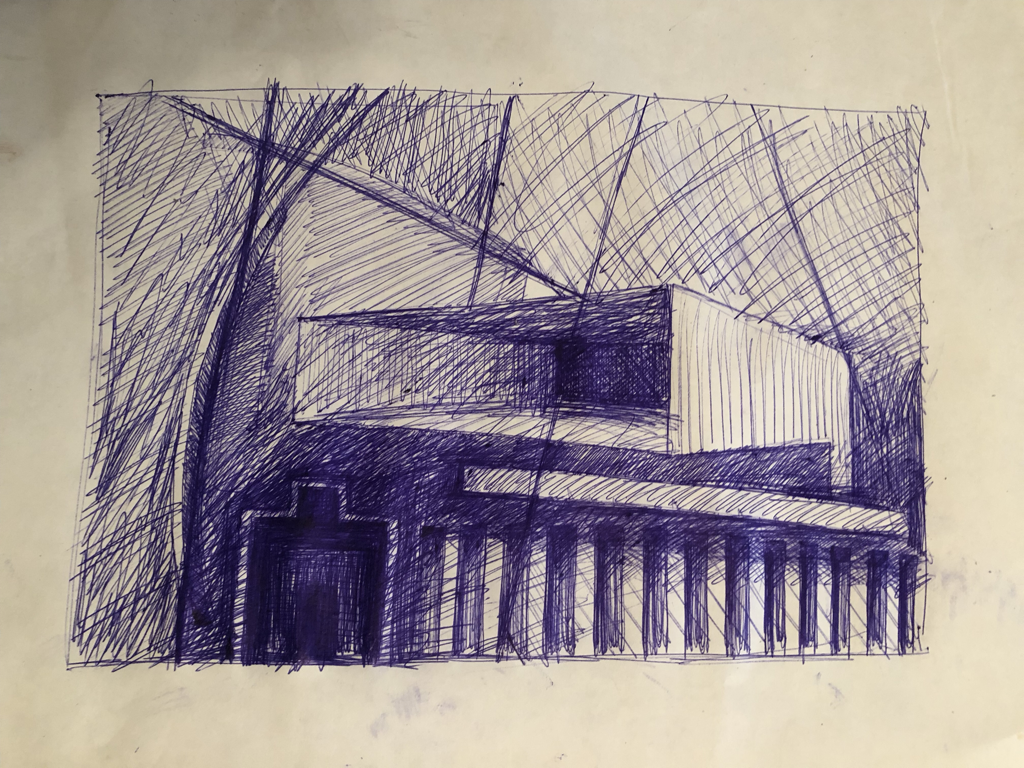

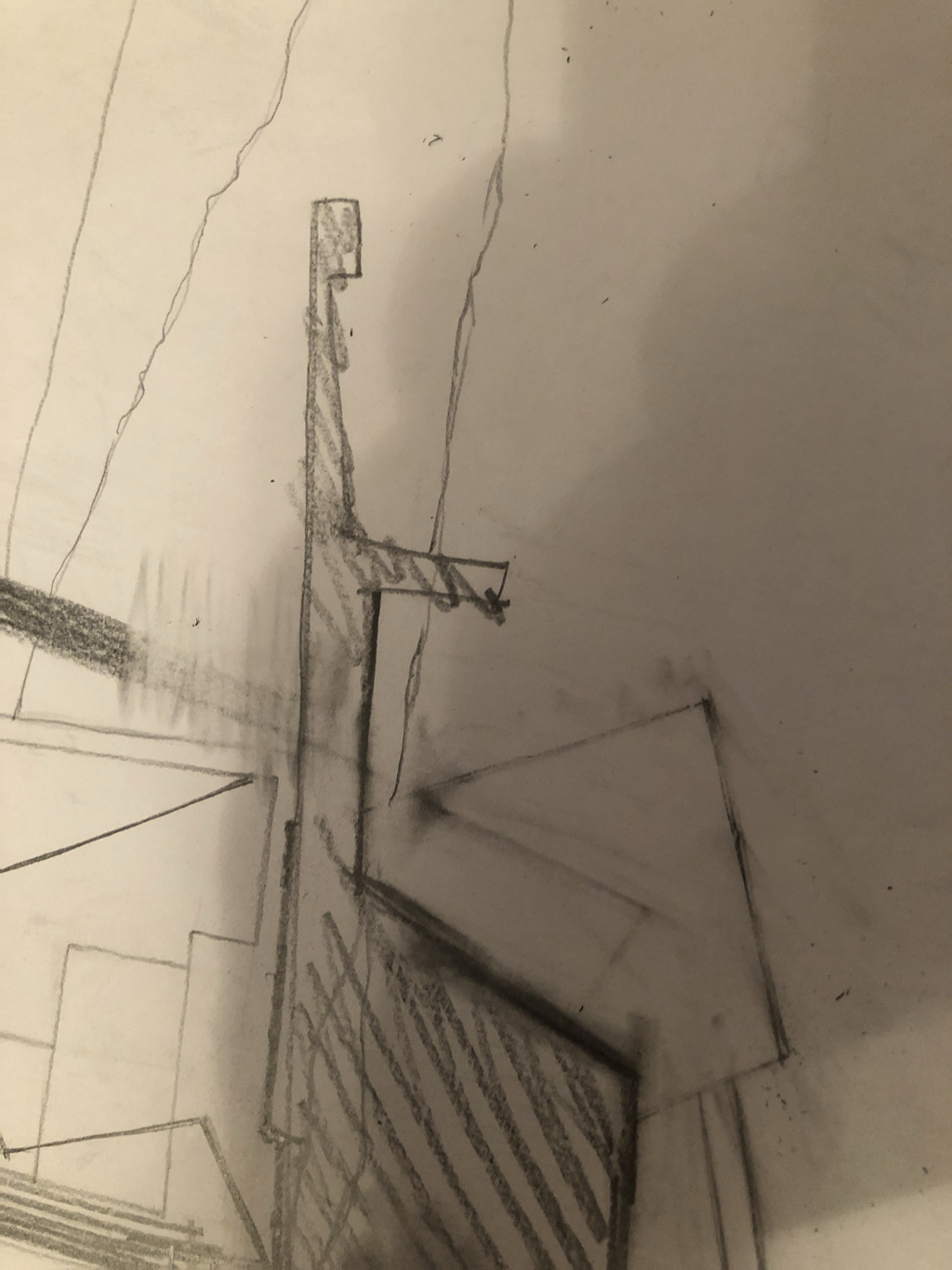

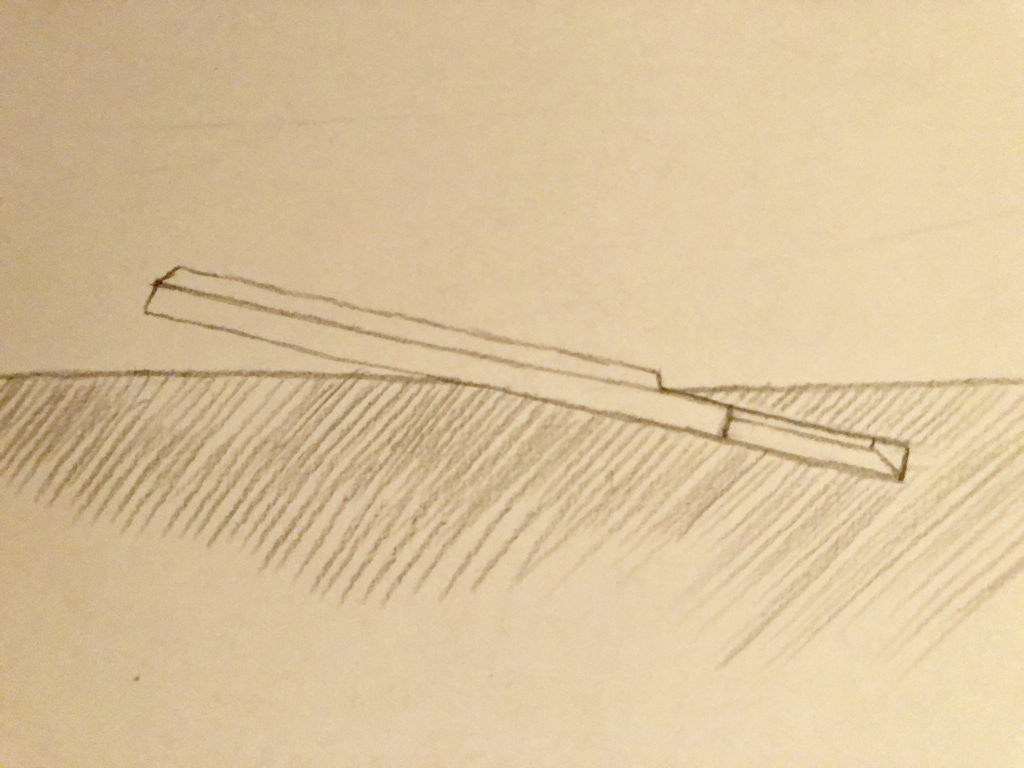

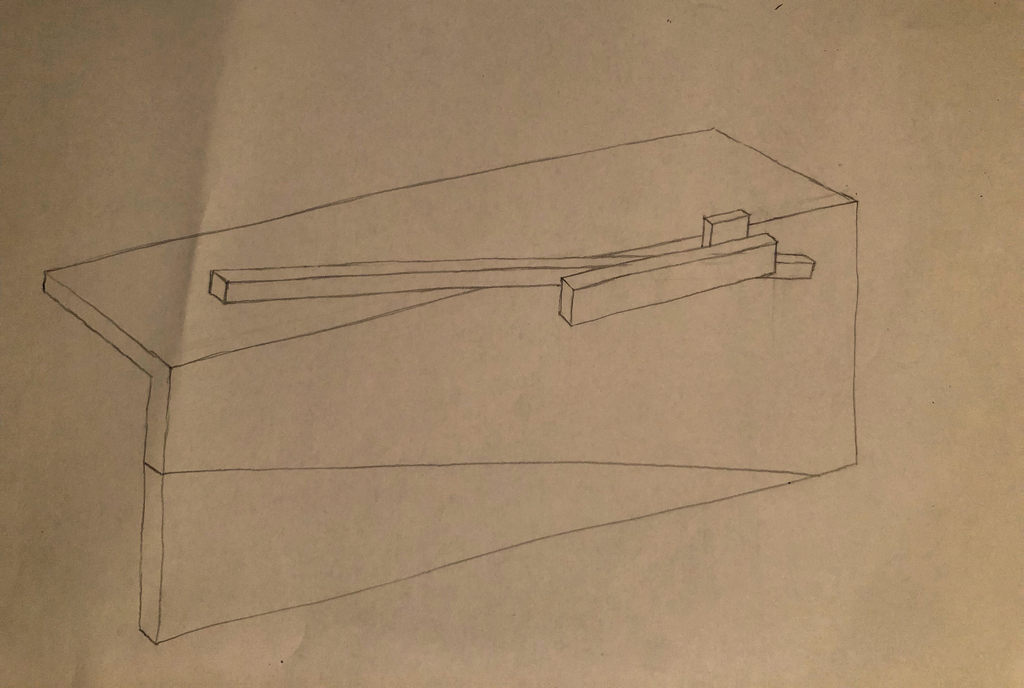

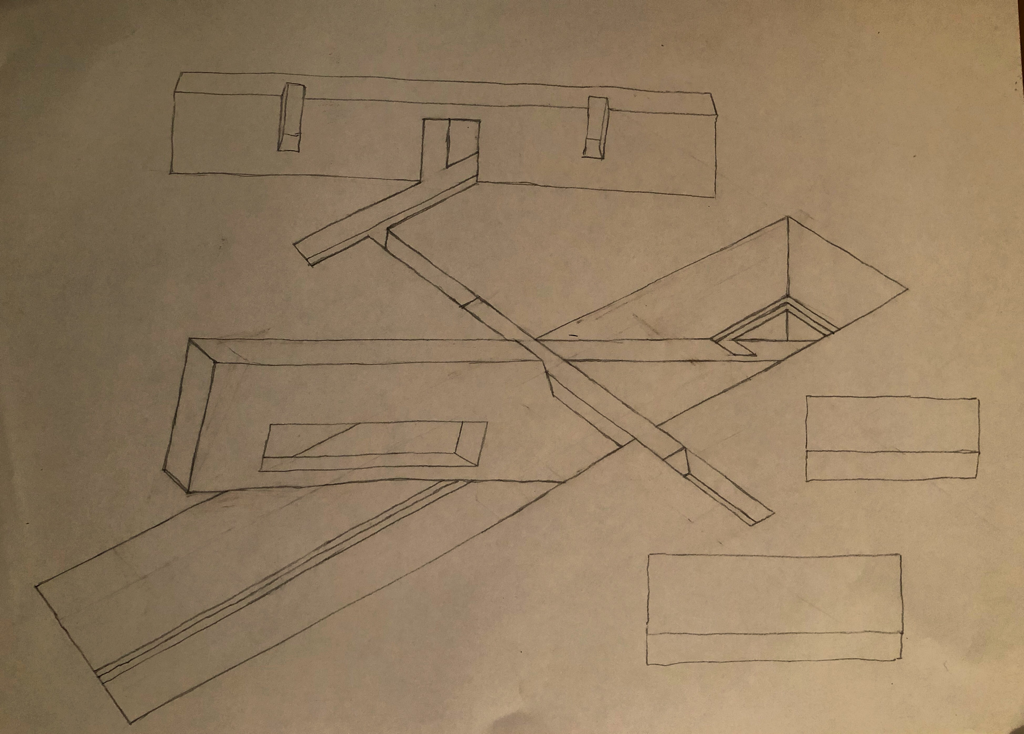

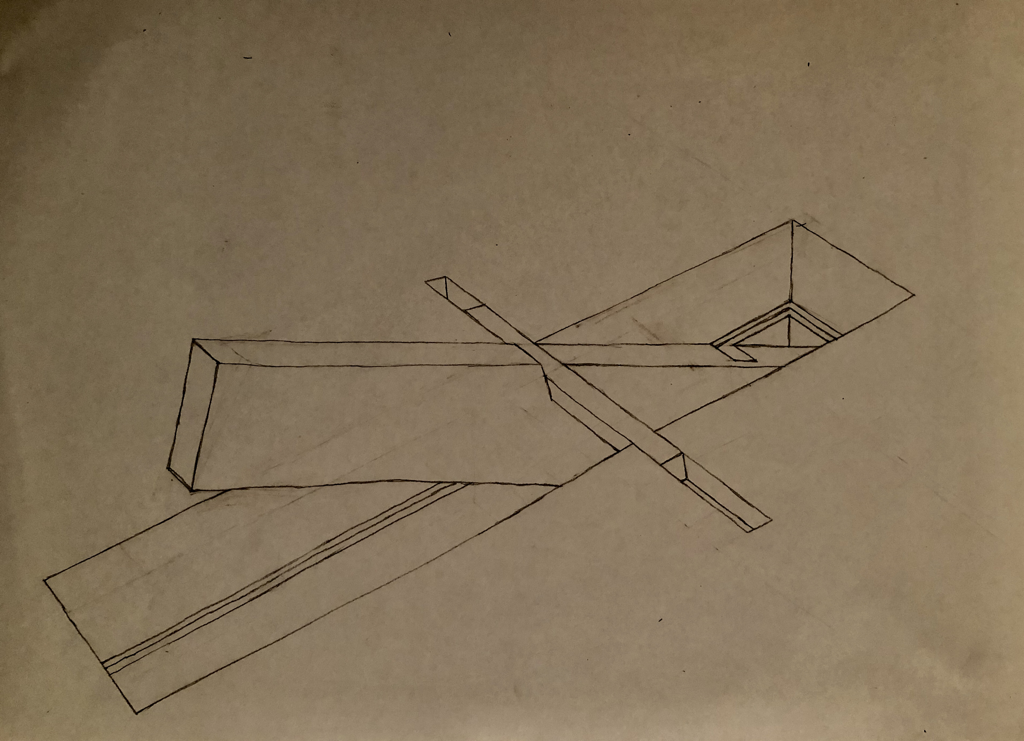

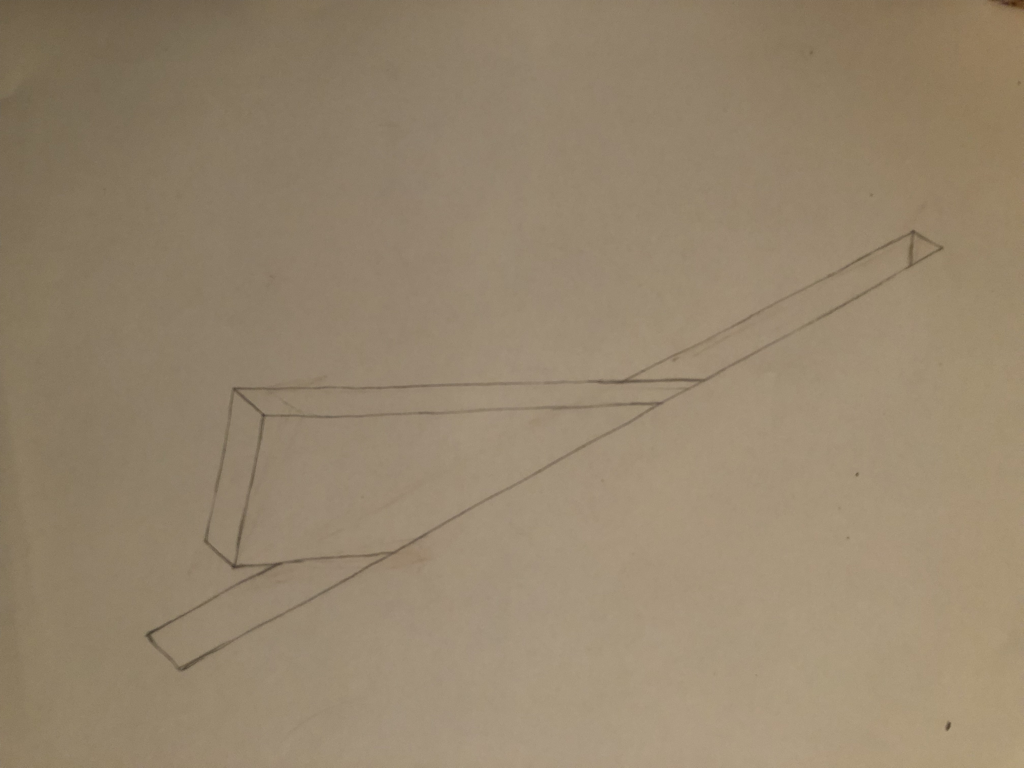

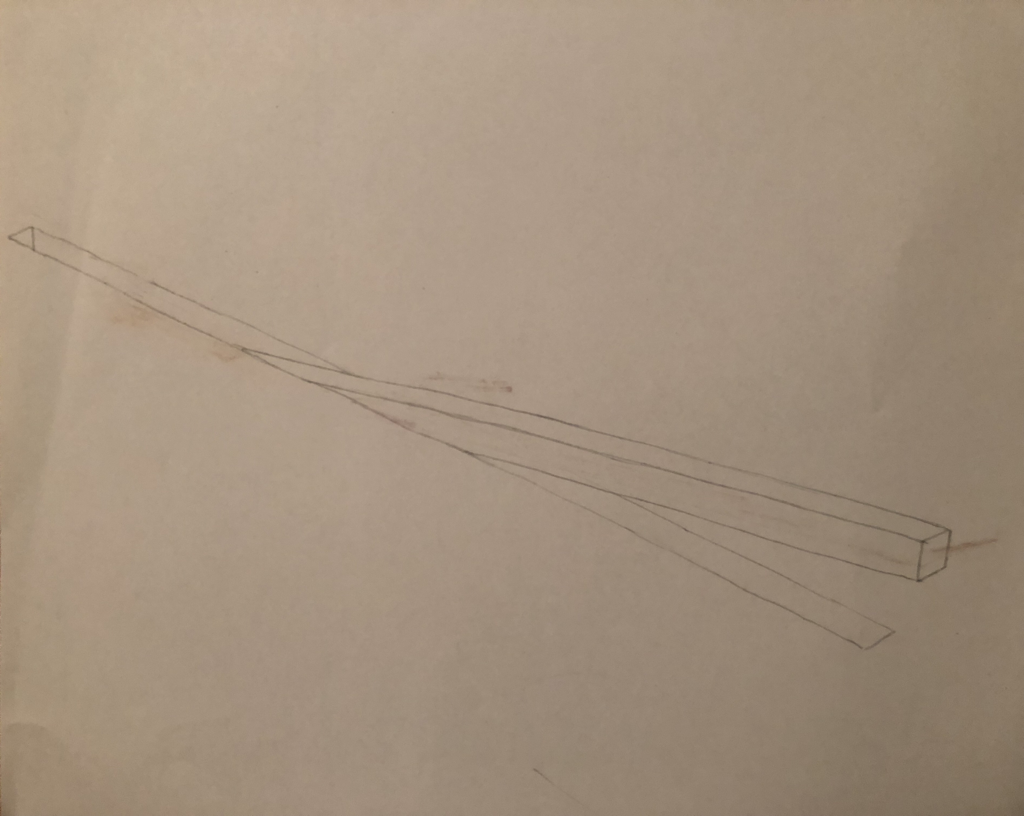

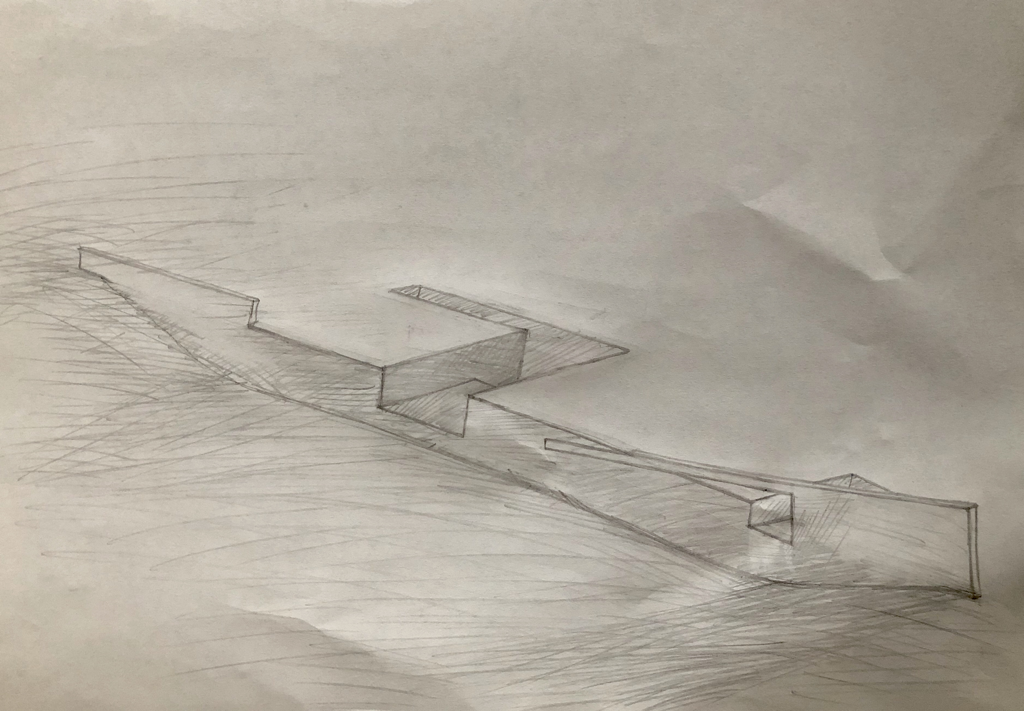

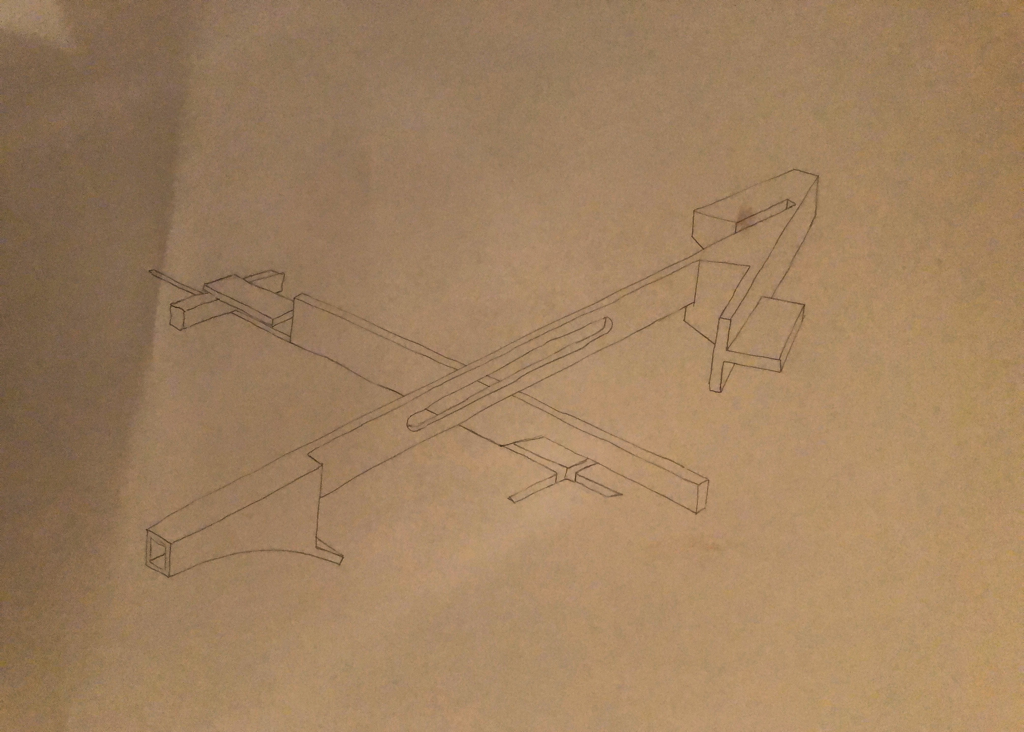

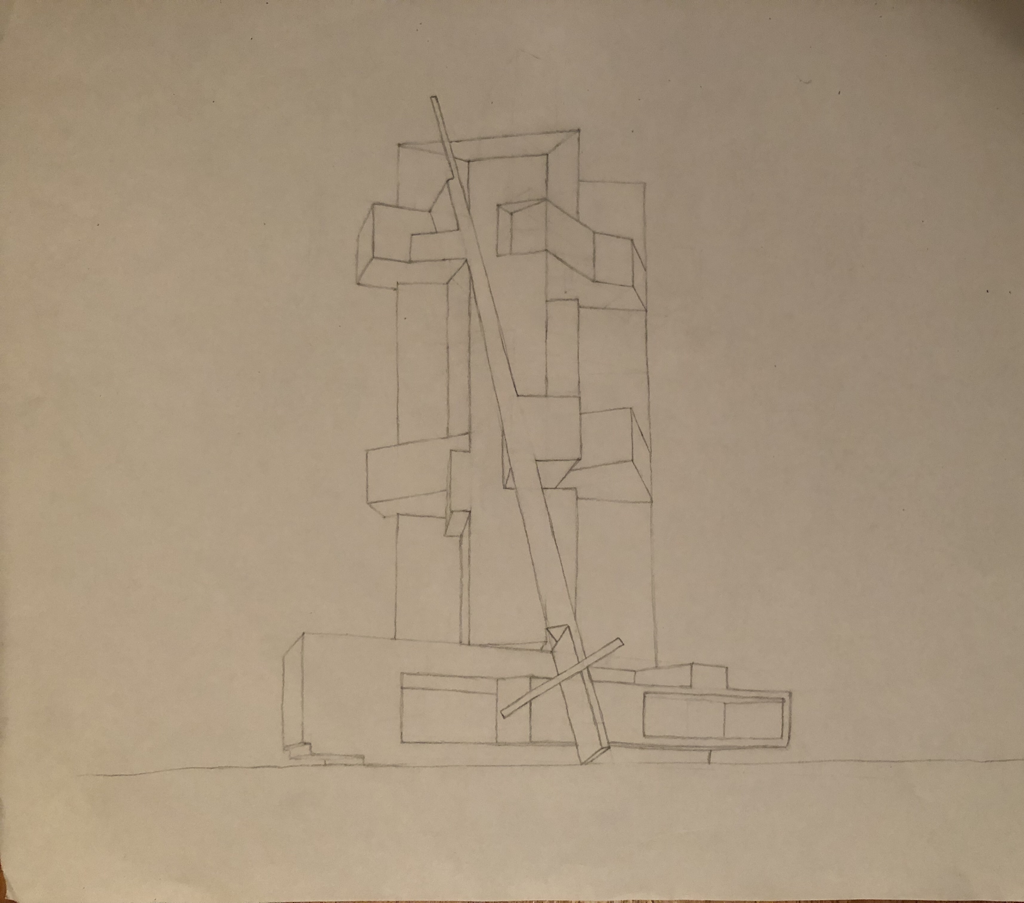

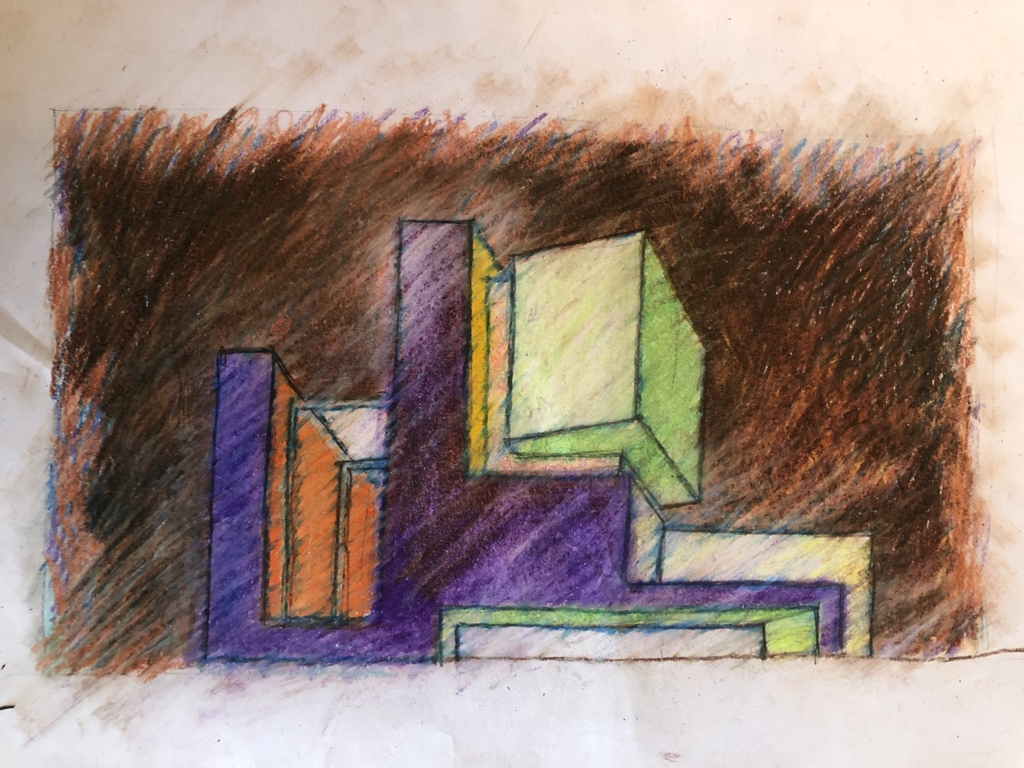

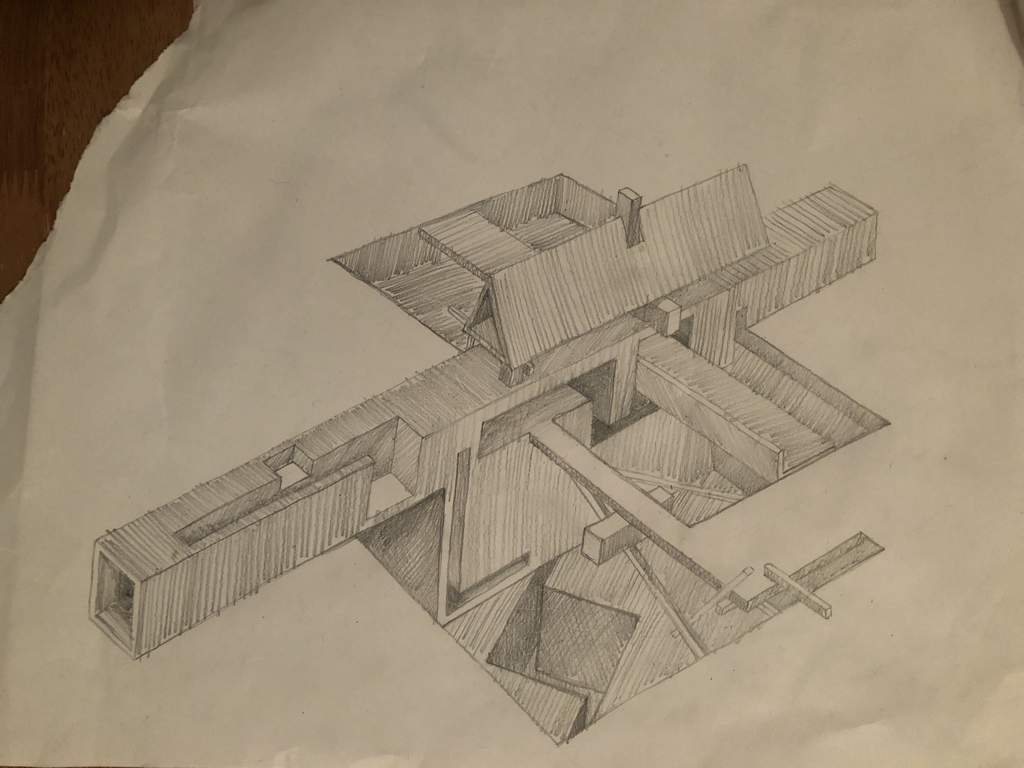

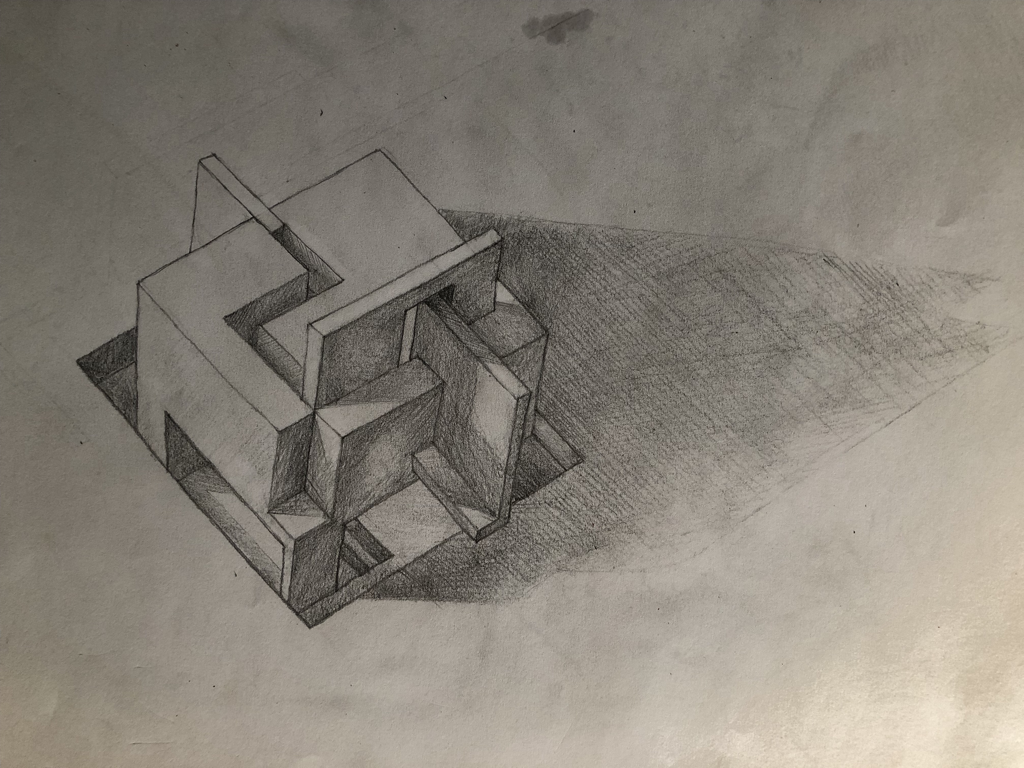

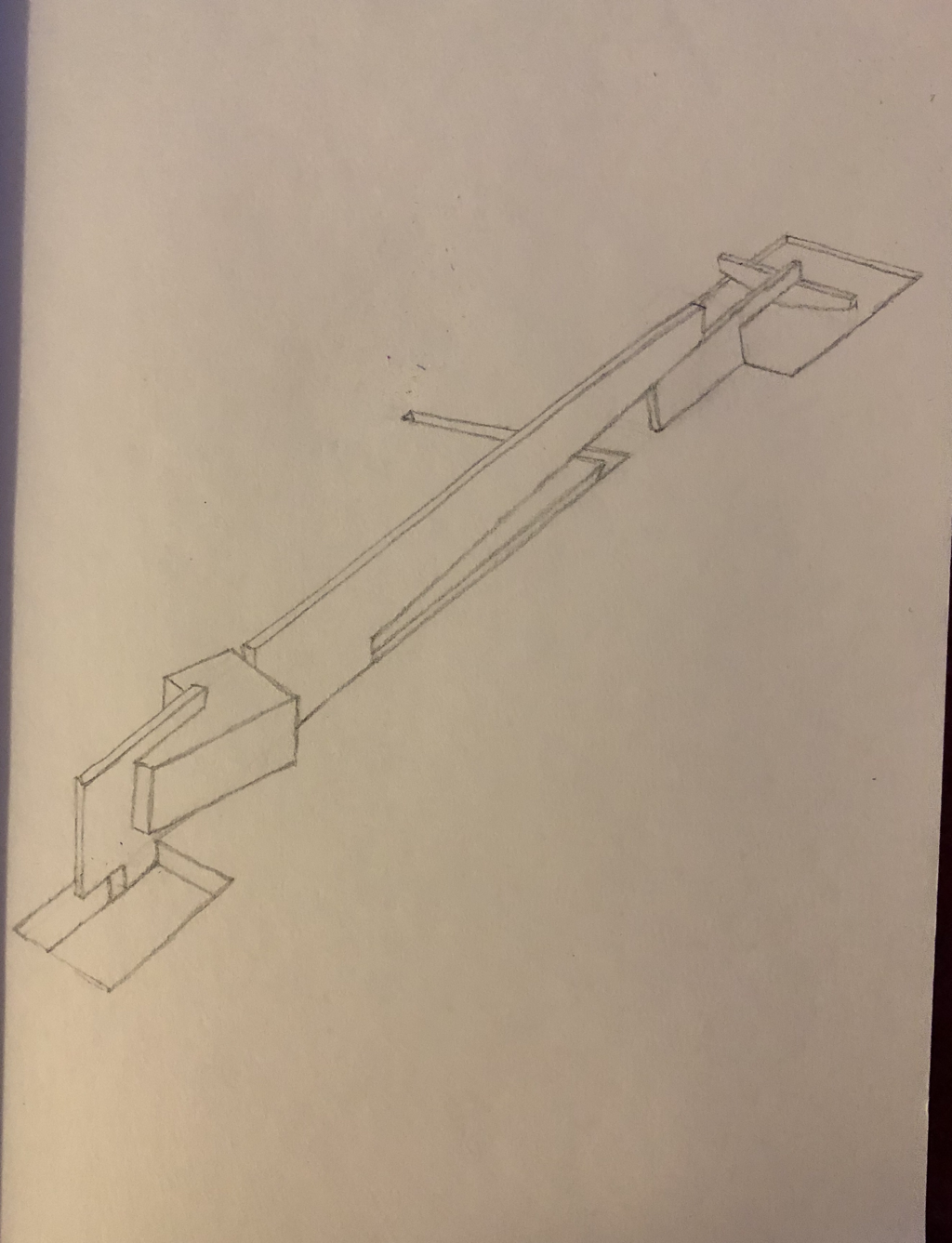

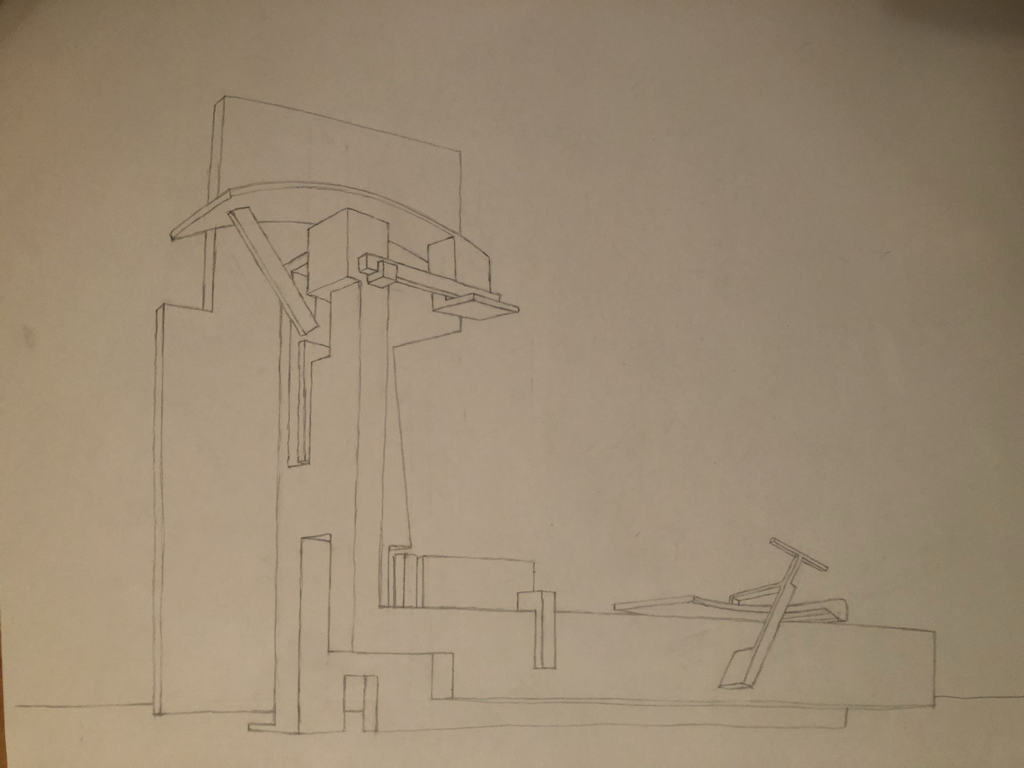

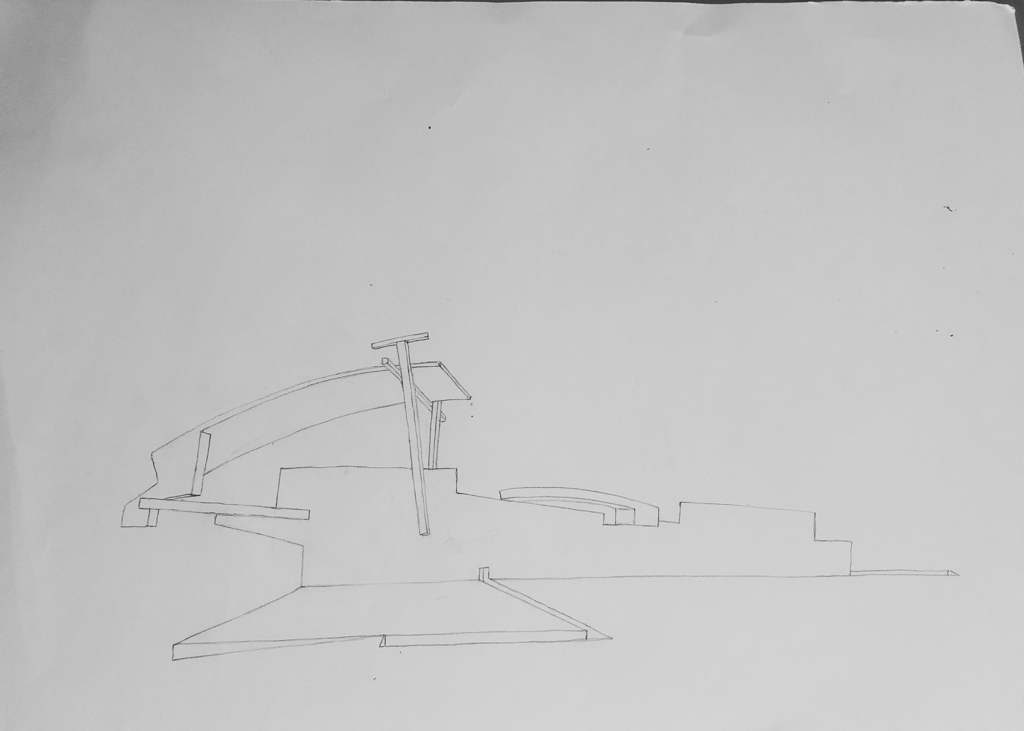

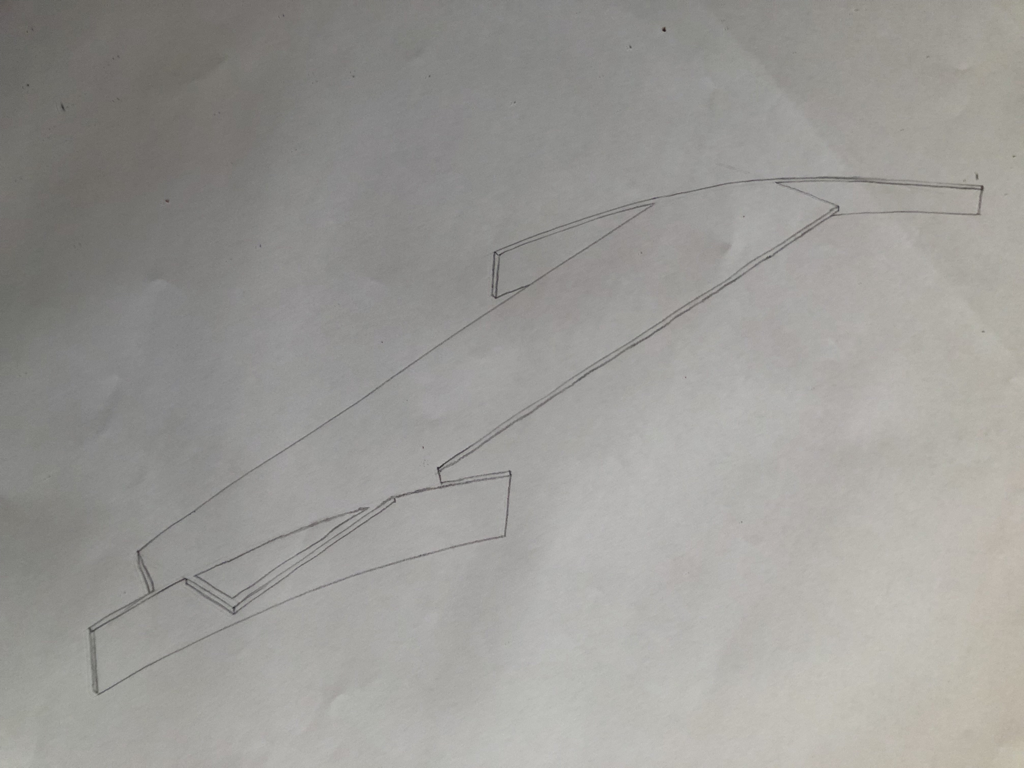

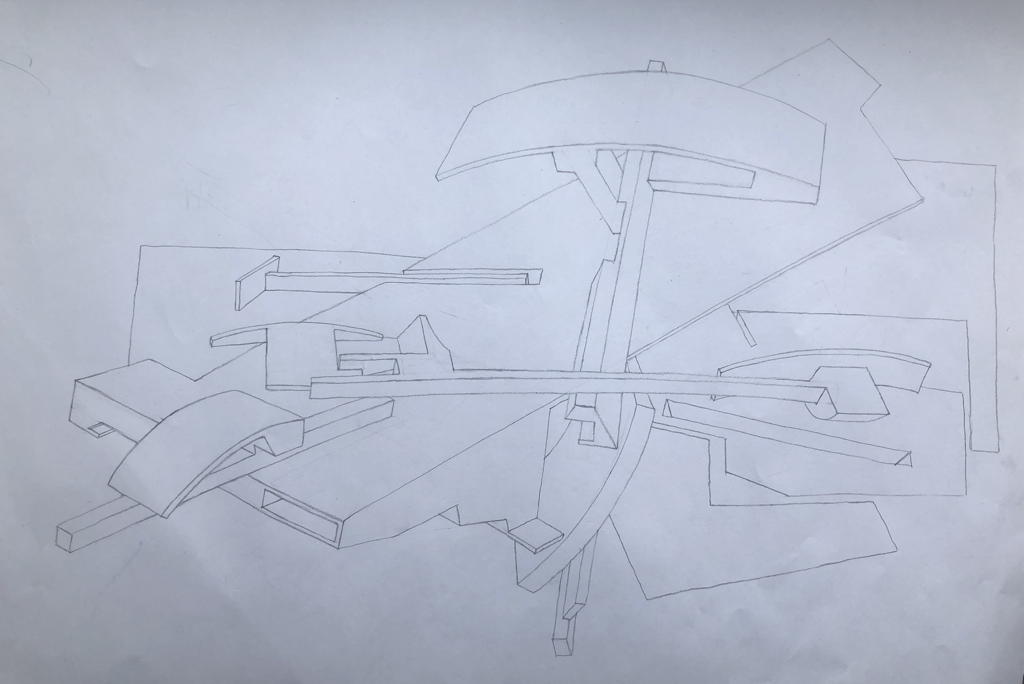

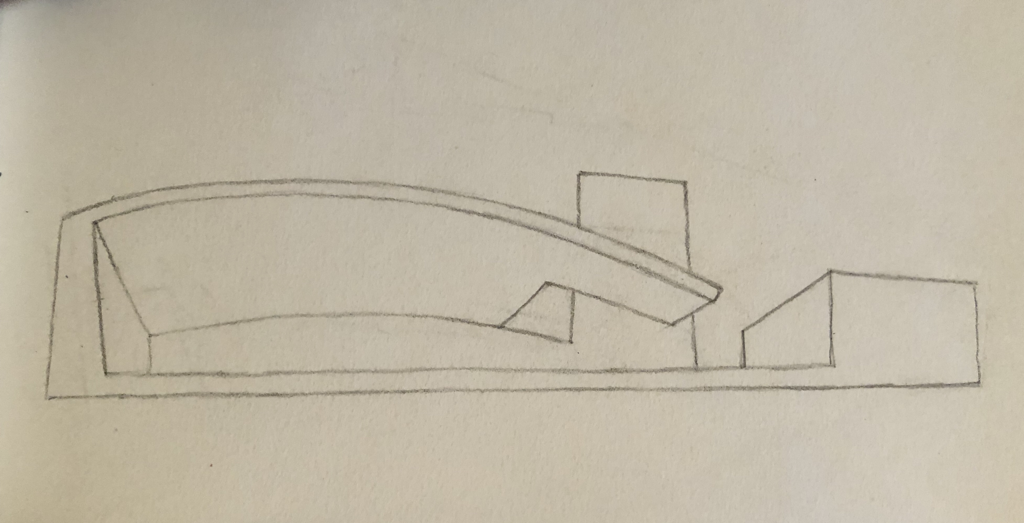

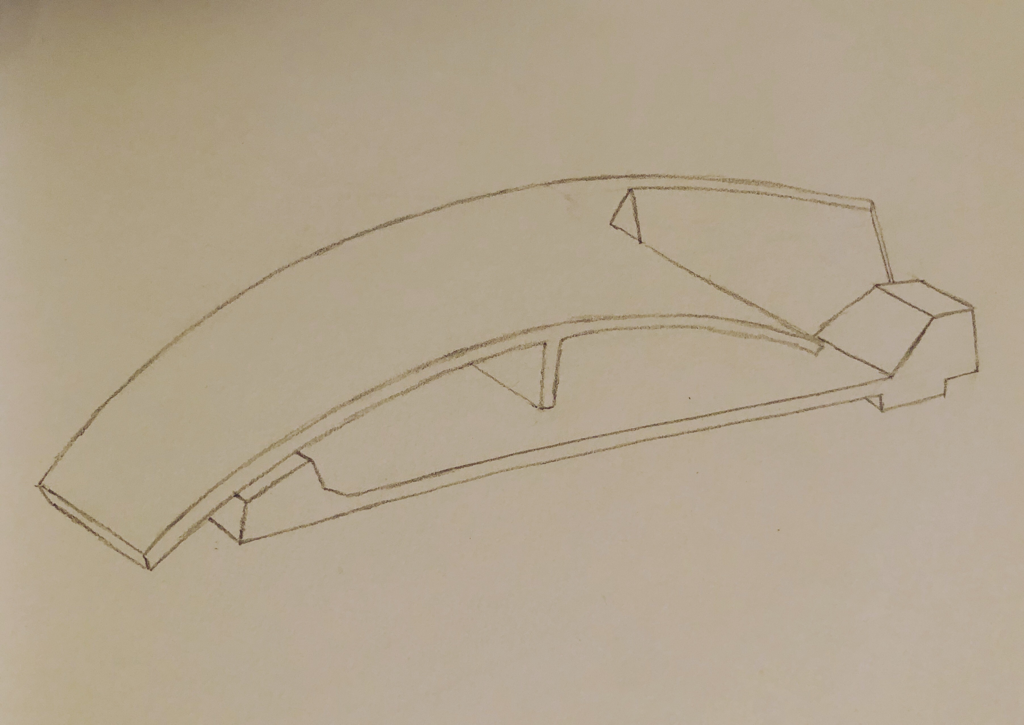

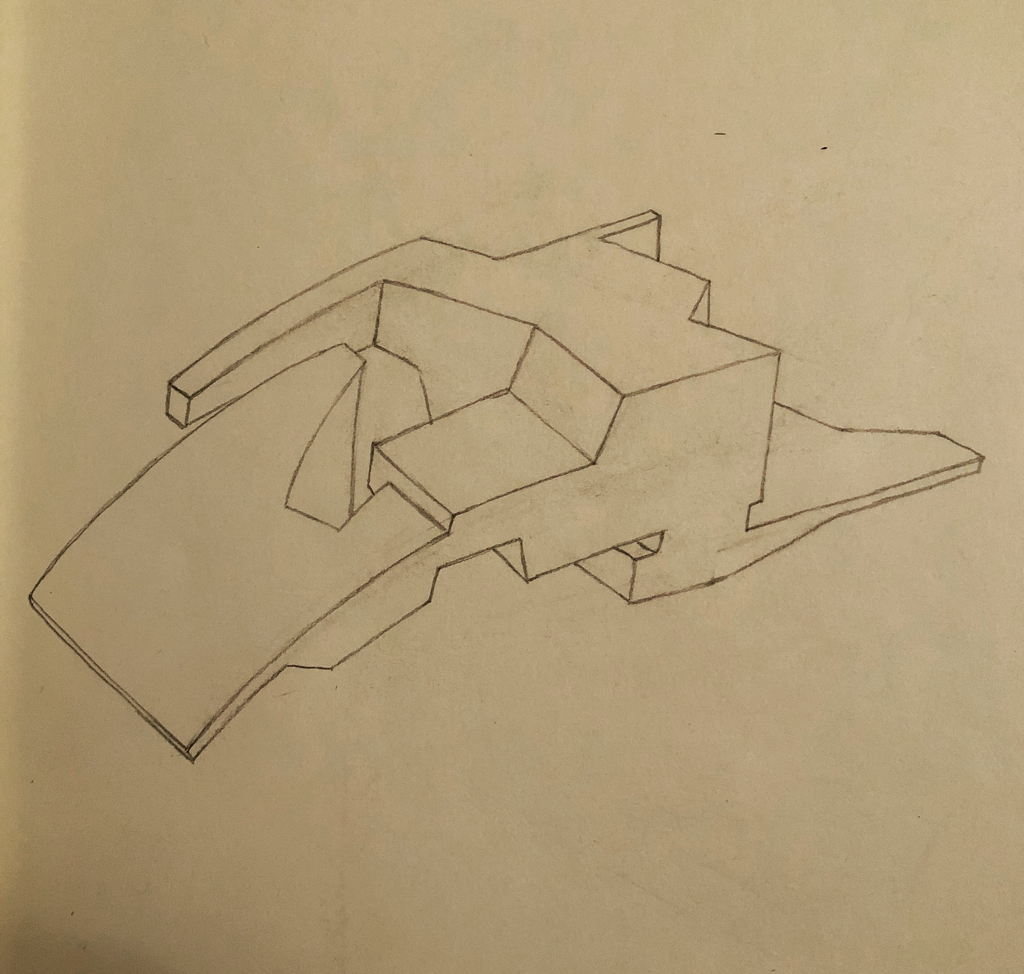

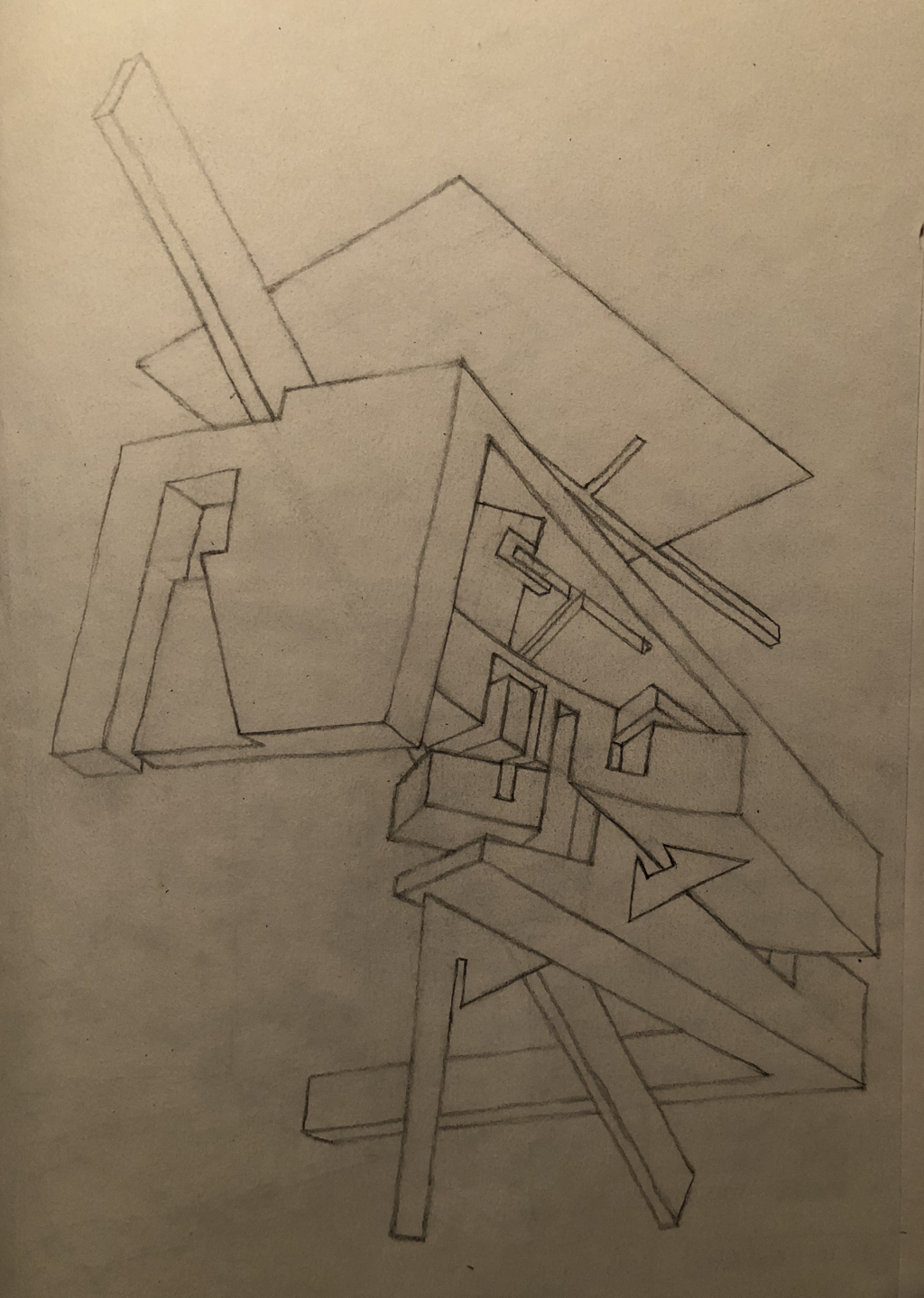

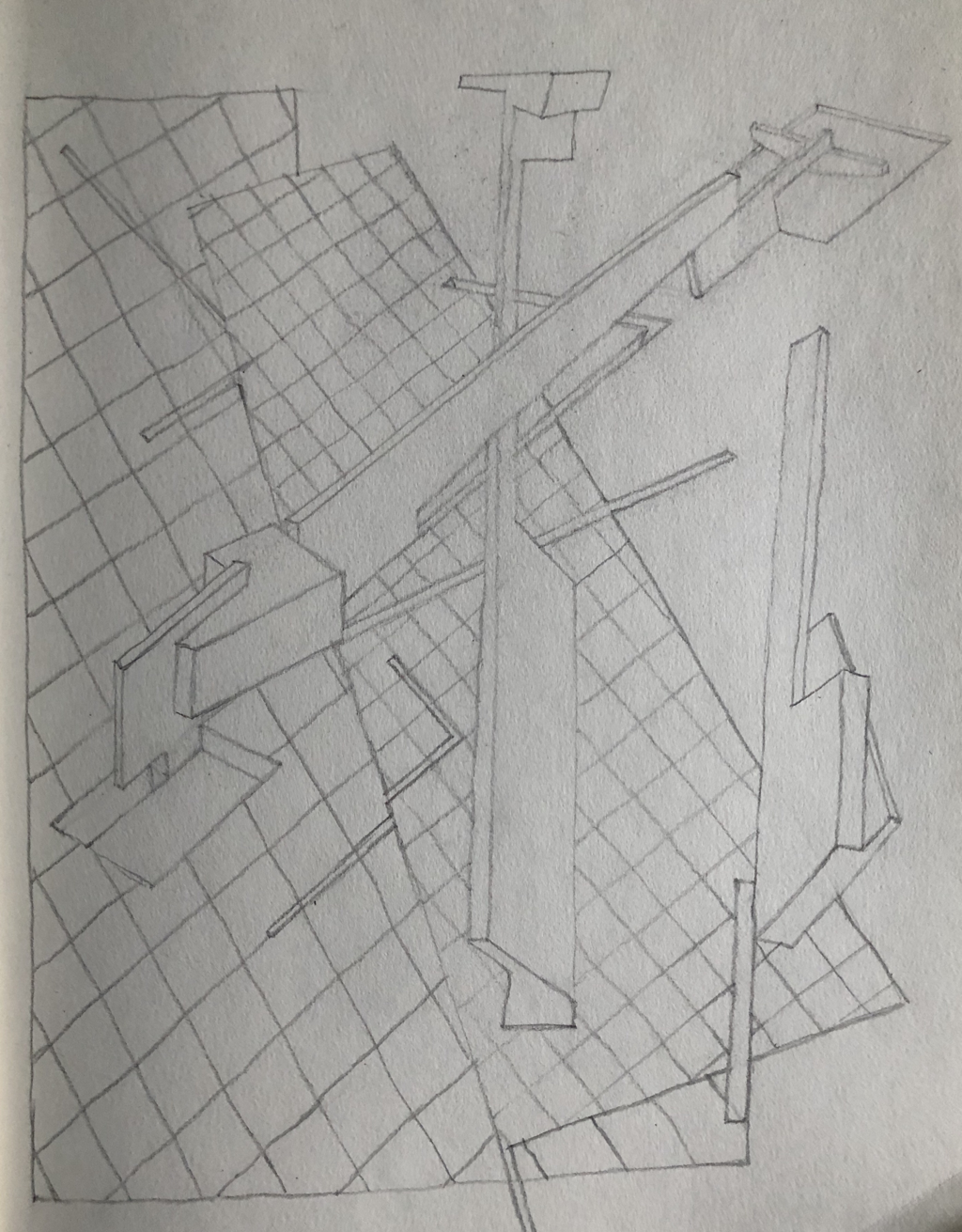

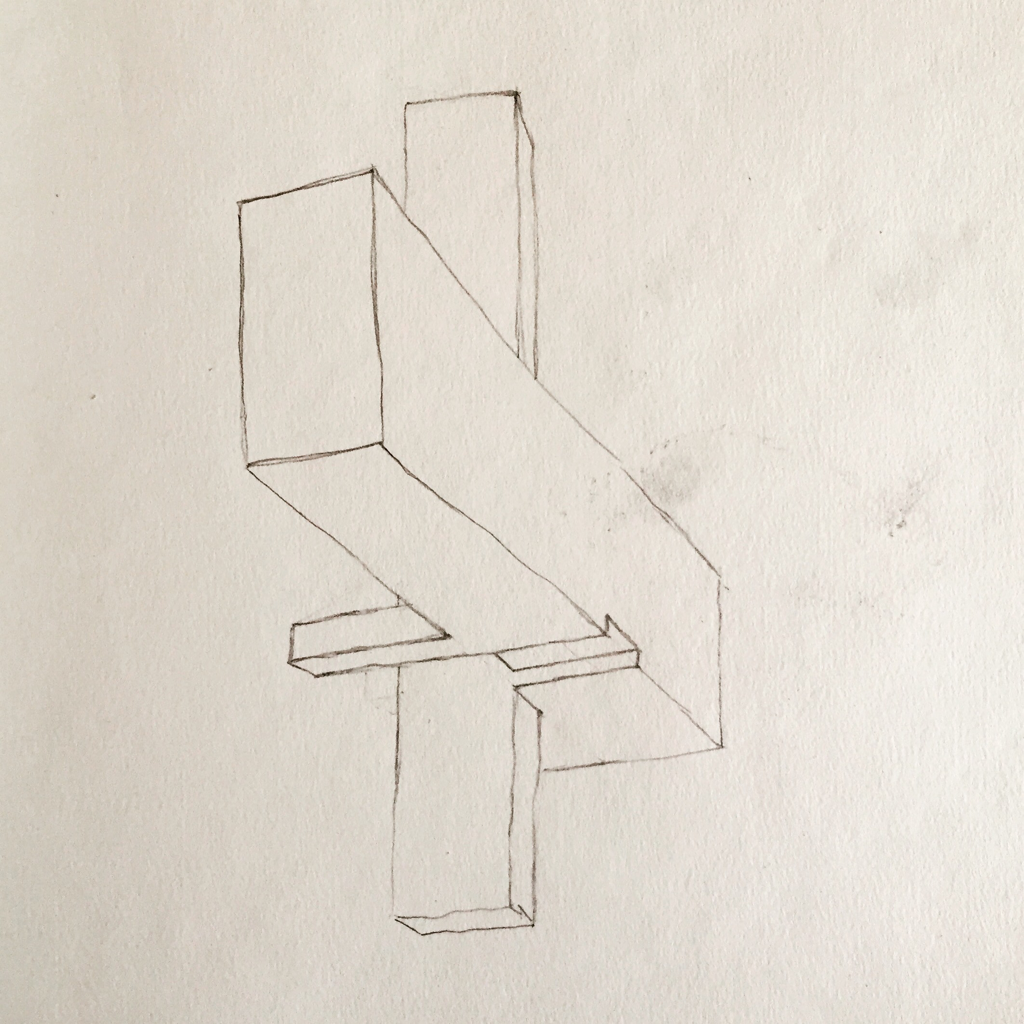

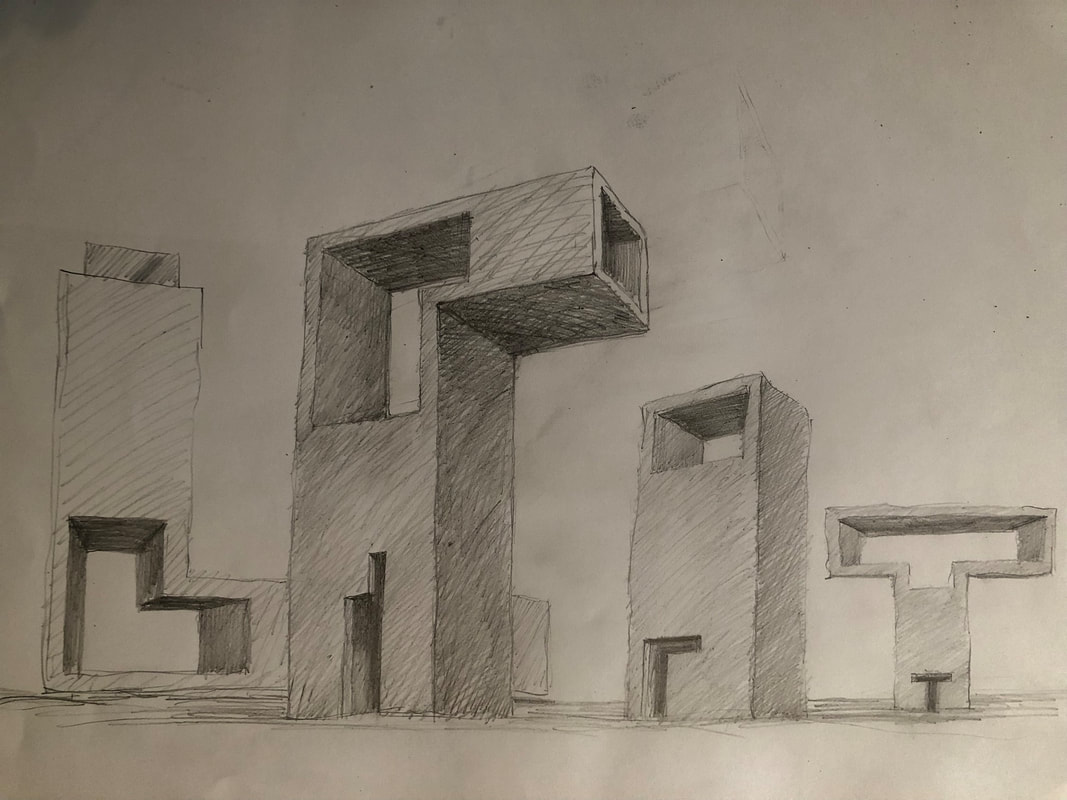

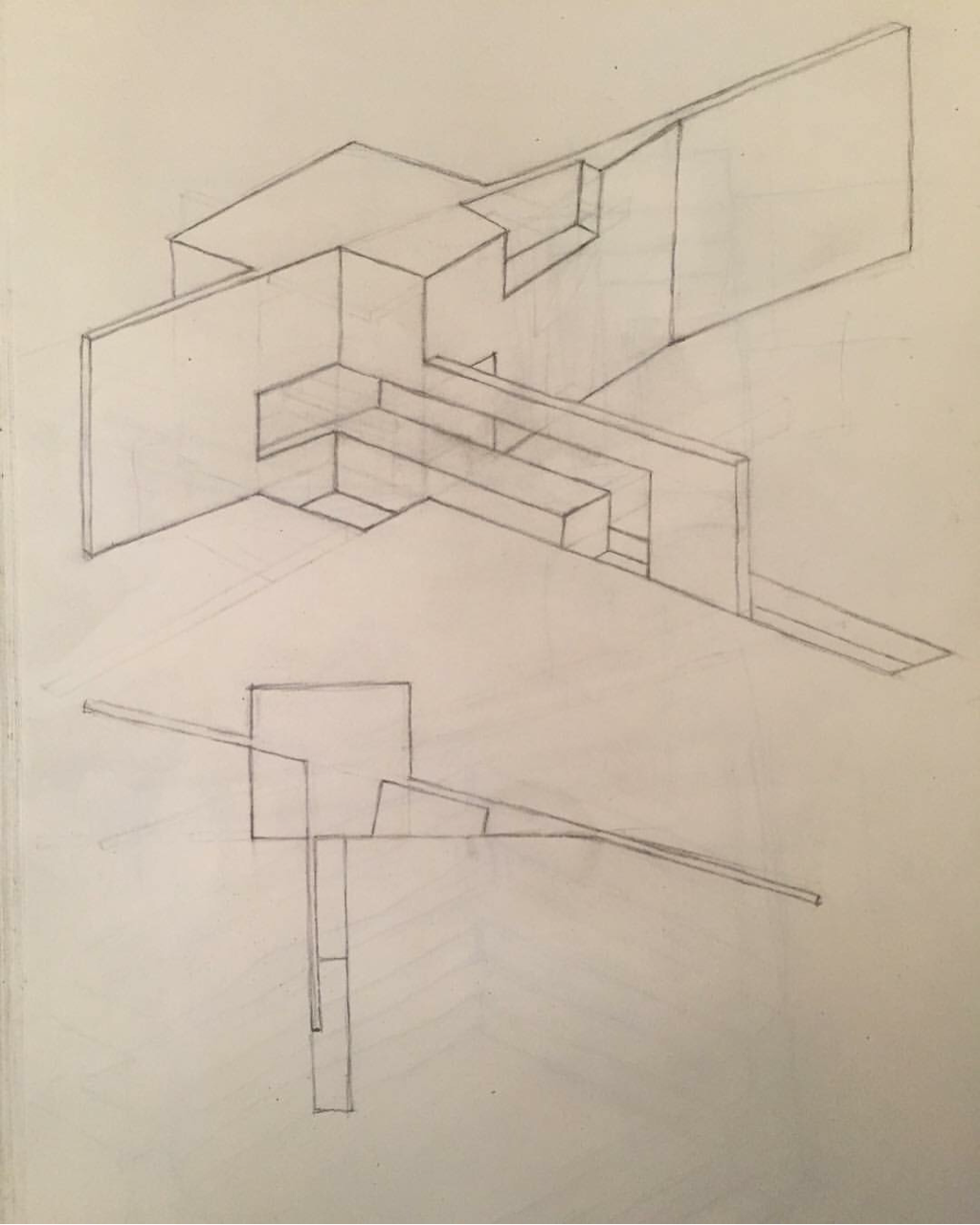

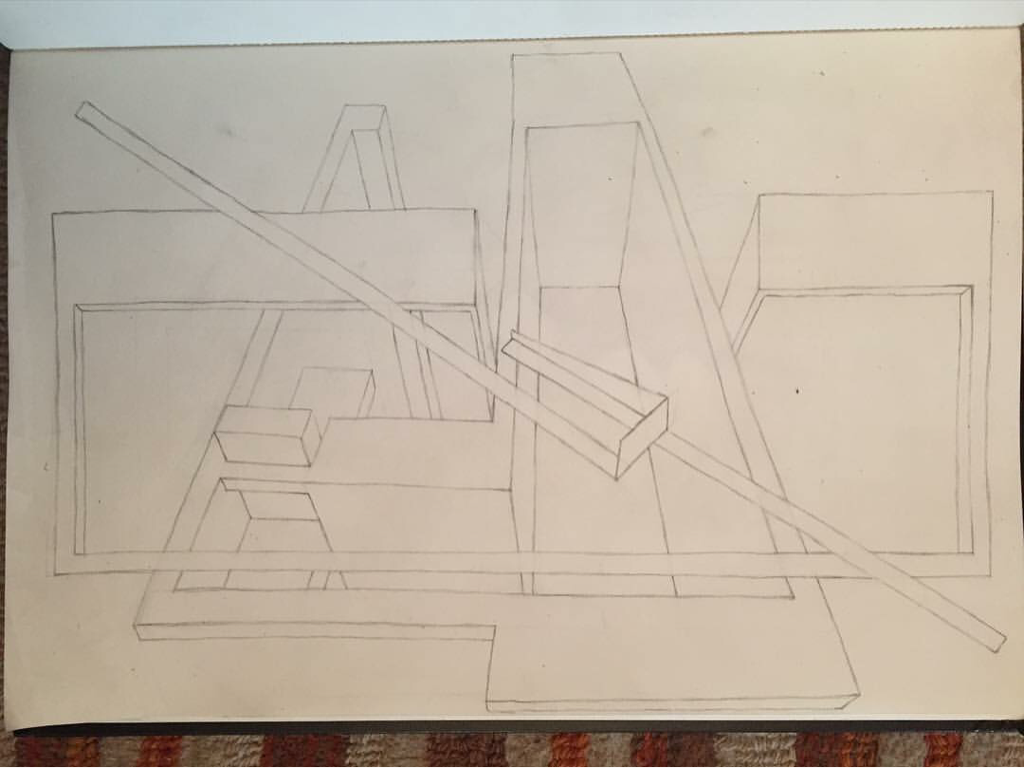

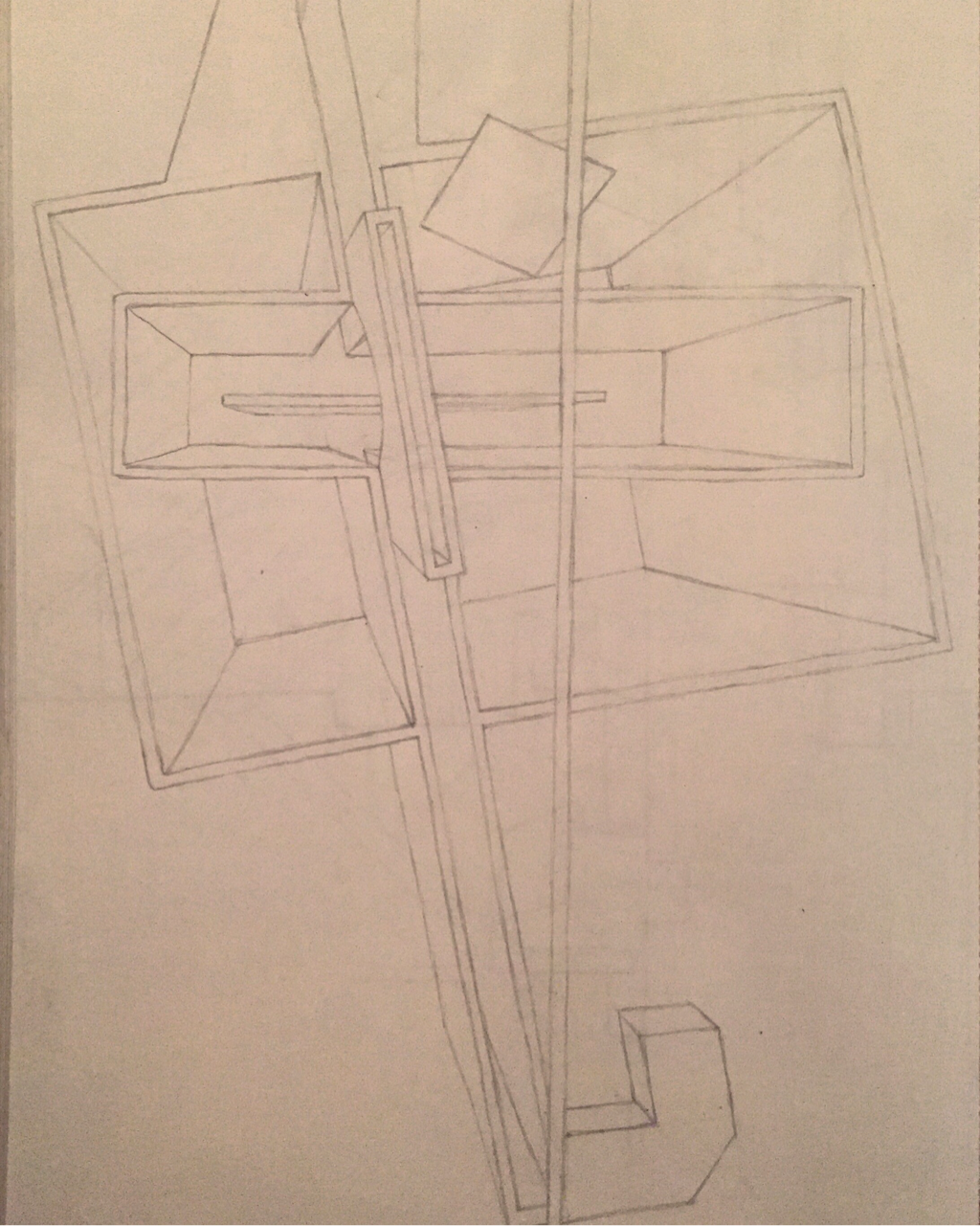

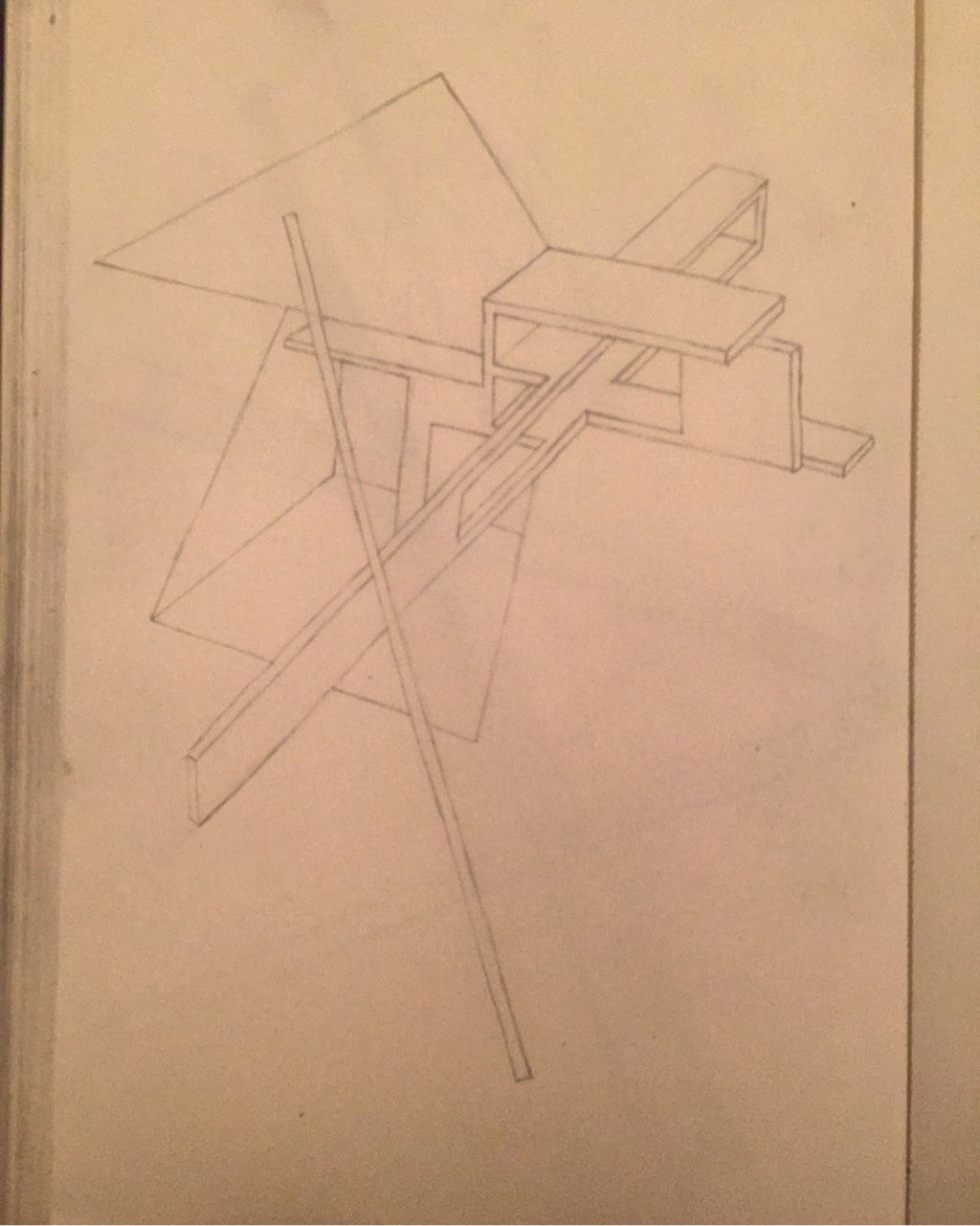

Acknowledgement from someone you look up to with awe and respect is like taking a creative tonic. And I think this building has way more chance of being built in the real world than any of the competitions I've entered. Here's a link to Tony's blog about his book. This is just a start and I'm still designing on the kitchen table with a pencil and A3 paper, it's a different house. Further development of the spaces will come over time and I will update on here. This is some text I wrote about the fictional gallery - There is an incision into the surface of the earth - buildings want to have a flat base. To minimise excavation the incision gently slopes up at 2.8 degrees or 1 in 20 - a gentle ramp. At the top of the hill the incision is 10m deep. Opening the surface creates a new space. Life wants to occupy the void. A series of objects are inspired by the fresh geometry - plates, planes and cubic objects. Diverse space is layered into the cut. Inside and outside, object and space blur. Stakes are driven into the wound to keep it from healing shut. Gallery space, external sculpture gardens, internal sculpture gallery's, cafes, auditorium, toilets, offices, storage occupy the line. Entry is made on the snaking road that cuts through the middle of the cut. Beehive MillThis blog post first appeared as a guest blog for Urbansplash. You can see it here. There are more photos here.

Beehive Mill is one of the first mills of the Industrial Revolution. Building commenced in 1824 and it is now Grade II star listed. It marks that time when people left their cottages and began working communally away from home. Liberation? Not in those conditions, but the home became home at least. I still find it mysterious that a building made almost two hundred years ago as a machine for the production of cotton can function so beautifully in a completely different age after another technological revolution with an unforeseen function. It looks obvious to us now, but imagine the building filled with enormous looms being powered by a steam engine. It is equally ironic that most of the tenants fill their spaces with homely objects and their dogs. A sense of domestic space is now conjured by the building when its original purpose was a counter to the cottage. Home, work and freedom reconfigured. Why do we love these buildings so much - what did those architects and craftspeople actually do and why do we enjoy it on such an instinctive level? How do we unlock that sense of well-being by bringing whatever it was they did forward into our time - to enable people to truly experience all that these buildings give us from a past where different things were valued? I've found it's not enough to just leave buildings as they are. They become pathological relics if left to their own devices. A layer from our time must be added in order to secure the future. Getting the balance of how we intervene is never obvious. I have observed that people enjoy this building for its authenticity. It expresses its structural components openly with minimal amounts of decoration. It seems to be a deep, instinctive force within us that resonates with materials that speak about their purpose. Brick holds up timber beams that hold up floors. Everything is there for a reason. My approach is to strip the building down to its primary components - almost like archaeology. Many years of layers were removed to reveal the original wooden flooring. Plasterboard and paint were stripped from walls allowing old bricks to see the light again. And then equally visceral new structures are added. In the reception space the original cobbles were uncovered and a new steel layer intervenes. This new layer folds and bends, forming itself into seating and tables. A strip of light always delineates the gap between the new palimpsest and the old structure. New functional elements are the places where a different game can start to be played. A cast in-situ concrete wall cuts across the grid at forty five degrees defining separate entrances and happens to be thick enough to house postboxes. A celebration of the everyday in a monumental form. It also happens by chance to be pointing due South - springing from an existing stair geometry. Toilets are different on each level. A slightly skewed personality to balance the rational repetition of the existing structure. Remember this building was the precursor to the Modern Movement in architecture. A functional machine with a grid of repeating columns. Its functional rationalism attracting like a magnet Sankey's nightclub - one centre of the counterculture - certainly in opposition to 'work'. Nothing on the night was as it seemed - moving artificial light bounced around disparate red and black surfaces. Every new door is different. The idea here is to reminisce about old doors then slice through the fabric of reality to form new opening to other worlds. Everyday objects are tilted slightly towards the uncanny. One tenant tweeted “We don't say we're going to the loo anymore. We say we're going to Narnia.” A young persons centre in Ancoats Conservation Area.

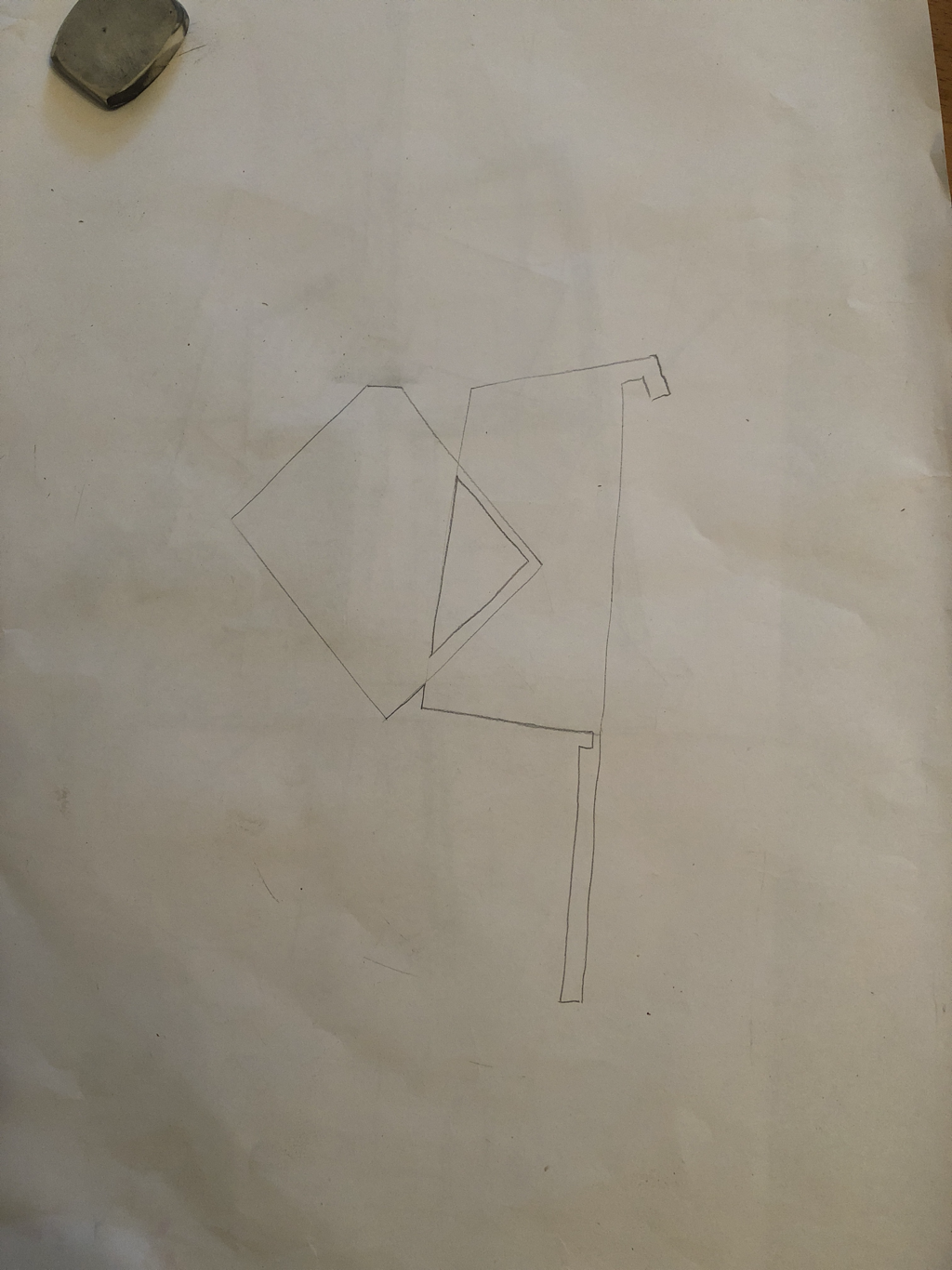

This project won Manchester Society of Architects Building of the Year, Manchester Chamber of Commerce Building of The Year and Best Innovative Design at the Northern Design Awards. It was published in the Architects Journal. My favourite critique was written by Karen Regn for Manchester Confidential and can be found here. My preoccupation with lines that cut across un-unified context can again be seen clearly in this project. This is the text I wrote about the building for the Manchester Society of Architects Awards submission : At the rite of passage into the adult world teenagers are possessed, particularly viscerally, by the relative world. The body is a vehicle for sensory physical, mental, emotional and spiritual experience......From this perspective imagine the profound, mysterious transformation happening at that time. The environment is seen through the vale of visceral fascination which flips from the sublime to the morbid - ecstasy to paralysing pain - excitement to boredom. As extremes of emotion are experienced, so the transition point in the middle is filled with confusion and uncertainty. Feeling........awkward / nothing fits in with demands / wants to change the world / can't bare fixedness / the body is changing at a rate never before seen / new sensory organs come on-line. Could a building reflect and help reconcile this transformation we all go through? A place they could feel 'at home' in - when the 'home' which they have loved throughout their life suddenly becomes alien - when the one place of security and protection becomes a restriction and the people you love who live there appear all too well defined. A building which offers security and familiarity, domestic in scale, but with unusual freedom - stable and yet free. A building which expresses duality - two opposing forces / geometries. The geometry of the site context containing a rebellious form which cuts through the site in a gesture of defiance. The site context provides a solid, familiarity.....a comforting brick environment with the almost domestic proportions of the Victorian shop and the Coates School building. The new building follows the existing urban geometry and forms a similarly proportioned three story end elevation to Jersey Street. Although the Pickford Street elevation is 'longer' in scale and more akin to its neighbouring MM2 development, it is still 'polite' and sensibly adheres to its contextual geometry. Inherent within the placing of the main accommodation at the back of the site, is the lack of a presence on Great Ancoats Street. The solution is to slice a link though the gap between the end of the Coates School and the gable of the MM2 apartment block, terminating at Great Ancoats Street as the point of entrance. The form of this link manifests itself as a 'leaning' wall wedged between the existing brick containment which continues on to slice though the orthogonal main building. In cutting the main building a triangular, double height, vertical space is formed, the stair cascades up the side of the wall completing the journey of circulation, always in relation to this 'rogue' angular gesture. From a conceptual perspective this rogue element will fuel a synergistic relationship with the centre and its not so old, not so square, visitors. The main accommodation building is orthogonal, rational and simple in its expression, this is to provide an overall stability and will enhance the juxtaposed angular sliced leaning wall. The windows are all orthogonal too, but are spaced in a random way. Again, this is to balance all the right angles, too many aligned grids can feel oppressive. The people who ‘are’ 42nd Street have become particularly adept at dealing with the desire to self harm, to cut in order to express or release powerful overwhelming forces. Inherent within this desire is the notion of balancing, curing with like for like, violence cancelled by violence. Leonard Cohen wrote the lyrics: ‘There is a crack in everything - that’s how the light gets in’. To release this building from its completeness as a ‘box’ a 17M long glass slot slices through its core - that’s how the light gets in. Such vulnerability as this must be protected at all costs, it’s what keeps us straying too far from ourselves. Four steel Sentinels stand guard, they demand / inspire your attention and clarity of heart, before you pass into this modern manifestation of sacred space. Once inside be prepared for the unexpected: tapering stairs, angled rooms, leaning walls, a corridor to nowhere - and wardrobes which are passages to the psychologically protected land of one to one therapy. I recently had a Planning Application rejected. I've had refusals before, but this one was different. The Application was for an extension to a typical 1930s semidetached house on Bancroft Avenue in Cheadle Hulme. I knew before the application went in that the Planners were going to recommend rejection on the basis of architectural style alone. I had already submitted a Pre-Application and from the feedback had ironed out any easy-to-reject rule breaking. This was going to be about aesthetics. I asked some friends to write me letters of support. Stephen Hodder, ex president of the RIBA and inaugural winner of the Stirling Prize. David Rudlin who is Chair of the Academy of Urbanism and winner of the 2014 Wolfson Economic Prize - he has also written books about planning and urbanism. Craig Stott - who runs a unit in Architecture at the University of Leeds. Because of these letters the Planners were forced to go to committee so the Application could be decided by our elected Councillors. In an unavoidable twist of fate I ended up in A&E on the night of the meeting. This was unfortunate in light of what transpired. The Conservative chair Brian Bagnall set up an argument around what he called a measurable reason for refusal. The opposing Liberals felt the Planning officer Callum Coyne was being far too subjective in his eagerness to refuse. They argued that rejecting an application based purely on personal architectural taste is unfair. Brian Bagnall sidestepped this by inventing a false measurable fact. The drawings were sat in front of all who attended showing how the new extension was specifically designed so that the eaves of the new aligned with the eaves of the existing house. Despite this Brian managed to convince everyone there that the extension was higher. The Planning officer who knew the truth wholeheartedly confirmed this lie. The debate was over and the vote was to reject. A video of the meeting is here. Item 5J - 15 Bancroft Avenue can be found in the agenda column on the right hand side - https://stockport.public-i.tv/core/portal/webcast_interactive/321992 I did write to the thirteen people in the meeting pointing out the error, but I only received one reply from Councillor Suzanne Wyatt of the Liberal Democrats. She was supportive of the scheme and voted for Planning Approval. I was expecting a refusal. The position of the Planners was made very clear at the pre-application stage - 'If you don't replicate the building technology used ninety years ago to construct the original house we will refuse'. What I didn't expect was the debate within the councillors meeting for such a small project - it was very clearly about style, about personal opinions. At one point I thought it might even get an approval. Brian put an end to this as described above.

Matt and Sam, my clients, also expected a refusal and we always intended to go to Appeal. But the way it was refused, based on a lie, was infuriating and unfair. And for this to go unacknowledged by the people in the meeting is outrageous. And why are these people who are the guardians of our built environment not listening to people as knowledgeable and experienced as David Rudlin, Stephen Hodder, Craig Stott and my myself? No mention of their support for a tiny house extension came up in the meeting. The young Planner who I would guess is in his late twenties who has never built a building in his life was talked about extensively and his opinions give huge weight. These men are in their fifties and sixties and have a lifetime of building Architecture. It is now the 19 July 2022, the hottest day on record.

I recently had a coffee with Julia Fawcett OBE, the CEO of The Lowry Theatre in Salford. To my surprise she had read my blog and wondered why I hadn't written anything since 2018. I didn't really have a good answer. When I logged in I found a draft from 2017. Here it is - A lot of the spiritual traditions say that there is only one thing. That the things we see as separate objects are actually all an expression of one continuous thing. An easy way to visualise this is to think about a computer. Do your files or movies have actual space in them? Are they discrete objects? No - they only exist as code that is arranged in a way that simulates our perception of real space. If all is one and separation is just an illusion - it must follow that opposites are the same - thing. The space in a video is code. The wall in a video is code. In the real world we think of solid objects in a very different way to space. Enlightened beings tell us they are the same thing. The universe is just one big event. The thing I have been preoccupied with in Architecture - from the beginning - is the choice to be rational or irrational. My degree thesis was entitled Irrational Rationalism. Do you build from an internal emotional, intuitive place or do you allow the external forces of an evolved system to dictate your work? The rational choice is to build upon what has gone before, to refine details that have stood the test of time in terms of function and aesthetics. it seems irrational to risk building new, untested ideas based on a feeling they might be of more value. Architecture literally shows us these two opposing forces frozen into its existence. We sense the conservative evolution of structures enabling the building to stand. And we are inspired by the progressive responsive ideas that fit the building into this particular context by resolving an enormous set of unique problems specific to this time, client and culture. All the great works of architecture I've seen feel like worlds or even universes unto themselves. No separate parts. No separation. |

Maurice ShaperoMy personal blog Archives

August 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed